Khasi folk tale : illustration Peacefully Kharkongor

Where is the country without its giant-story?

All through the ages the world has revelled in tales of the incomparable prowess and the unri-valled strength and stature of great and distin-guished men whom we have learned to call giants.

Our world has been a world full of mighty men to whom all the nations pay tribute, and the Khasis in their small corner are not behind the rest of the world in this respect, for they also have on record the exploits of a giant whose fate was as strange as that of any famous giant in history.

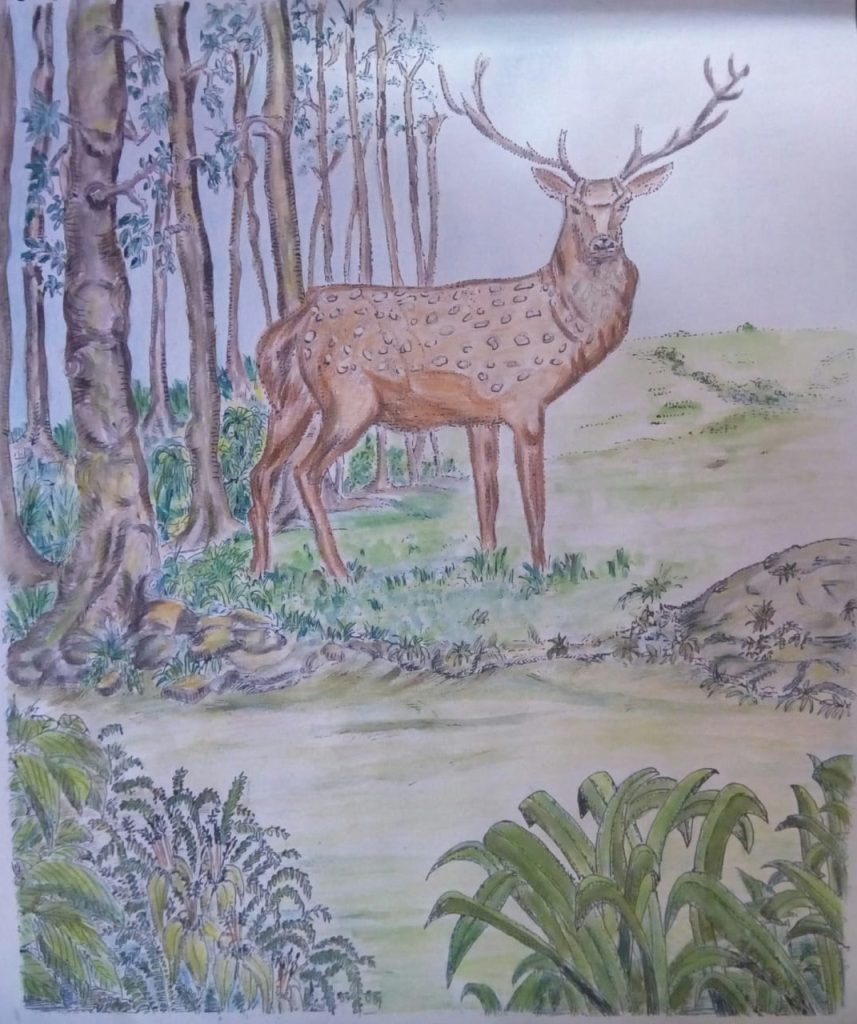

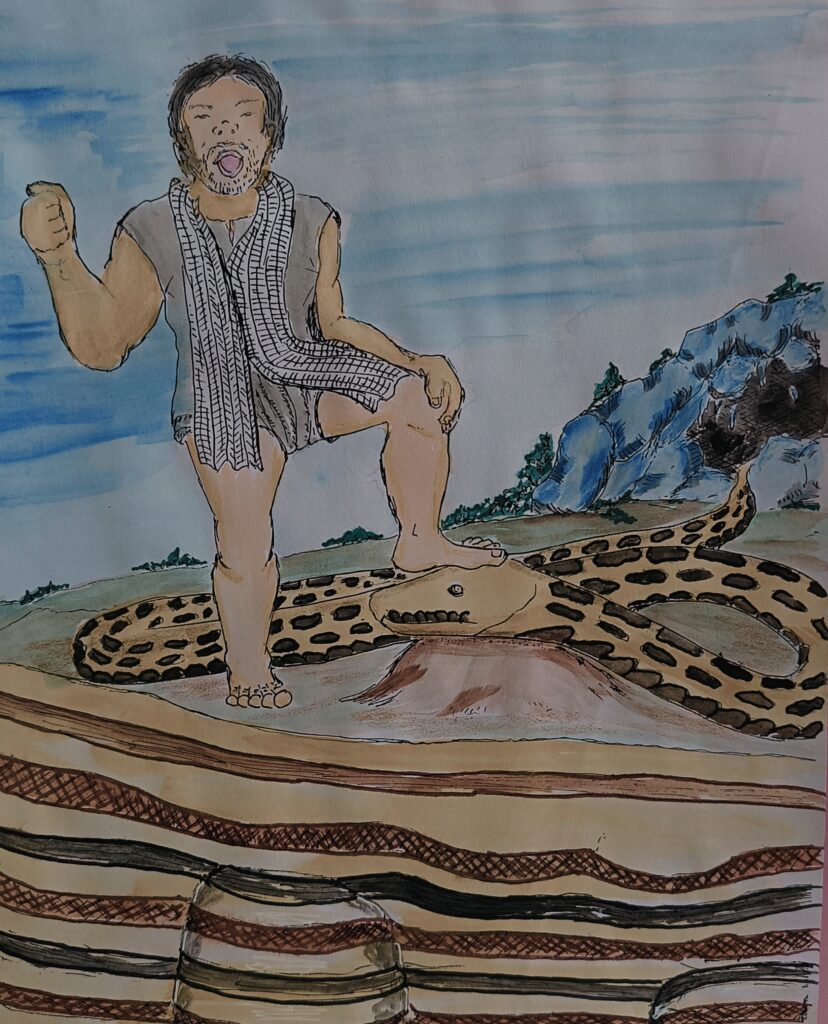

The name of the Khasi giant was U Ramhah. He lived in a dark age, and his vision was limited, but according to his lights and the requirements of his country and his generation, he performed great and wonderful feats, such as are per-formed by all orthodox giants all the world over. He lifted great boulders, he erected huge pillars, he uprooted large trees, he fought wild beasts, he trampled on dragons, he overcame armed hosts single-handed, he championed the cause of the defenceless, and won for himself praise and renown.

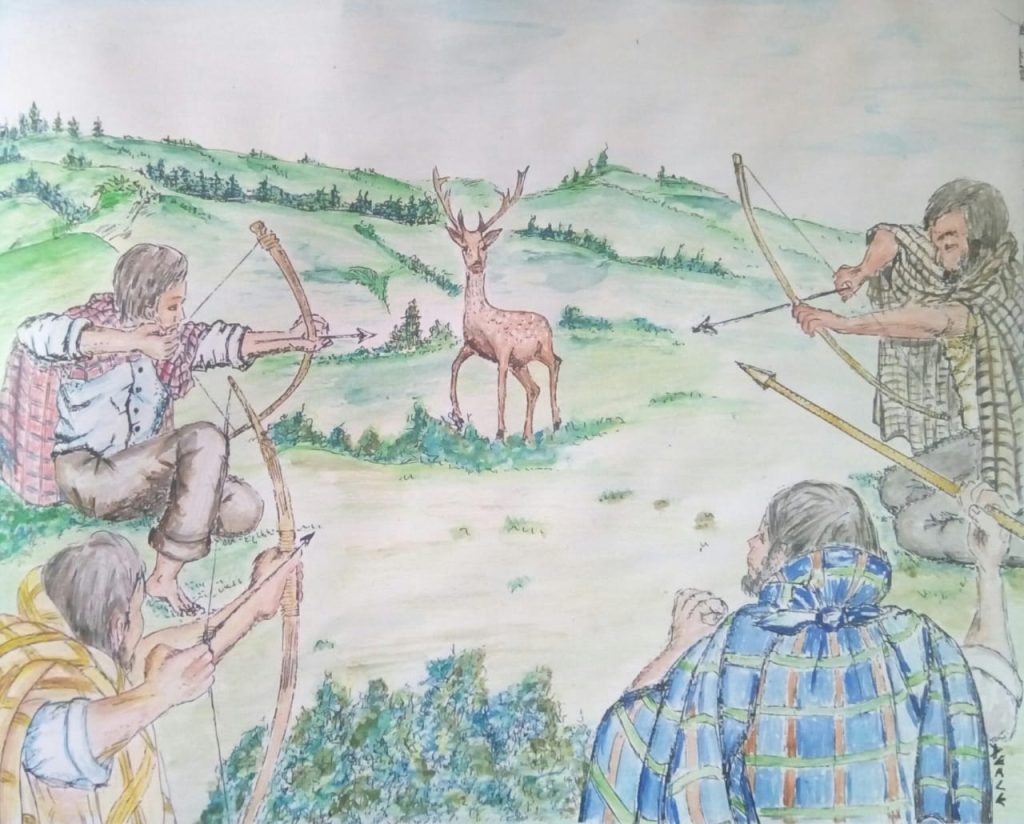

When his fame was at its height he defamed his reputation by his bad actions. After the great victory over U Thlen in the cave of Pomdoloi, he became very uplifted and proud, and considered himself entitled to the possessions of the Khasis. So instead of helping and defending his neigh-bours as of old times, he began to oppress and to plunder them, and came to be regarded as a notorious highwayman, to be avoided and dreaded, who committed thefts and crimes wherever he went.

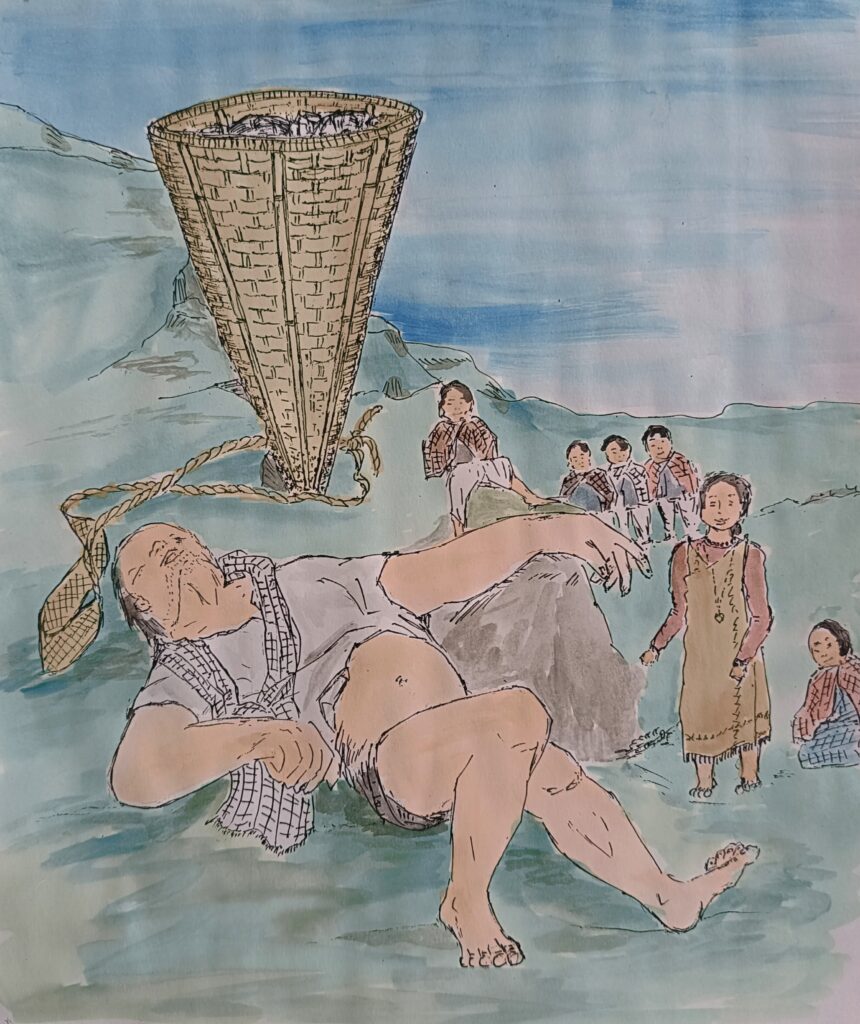

At this period he is described as a very tall and powerful man whose stature reached “half way to the sky, ” and he always carried a soop (a large basket of plaited bamboo) on his back, in-to which he put all his spoils, which were gener-ally some articles of food or clothing. He broke into houses, looted the markets and waylaid travellers. The plundered people used to run af-ter him, clinging to his big soop, but he used to beat them and sometimes kill them, and by rea-son of his great strength and long strides he al-ways got away with his booty, leaving havoc and devastation behind him. He was so strong and so terrible that no one could check his crimes or impose any punishments.

A wealthy woman named Ka Bthuh used to re-side in the village of Cherra. She had endured a great deal of suffering at the hands of U Ramhah and her resentment of him was intense. She had begged the men of her village to rise as one and exact revenge on those who had wronged her, but they had always told her it was pointless. She would point and shake her finger at U Ram-hah whenever they crossed paths, mocking him and stating, “You may conquer the strength of a man, but beware of the cunningness of a wom-an.” Because of this statement, U Ramhah de-tested her since it demonstrated that he had failed to overwhelm her in the same way that he had overwhelmed everyone else, and he raided her godowns more frequently than ever, not dreaming that she was scheming to defeat him.

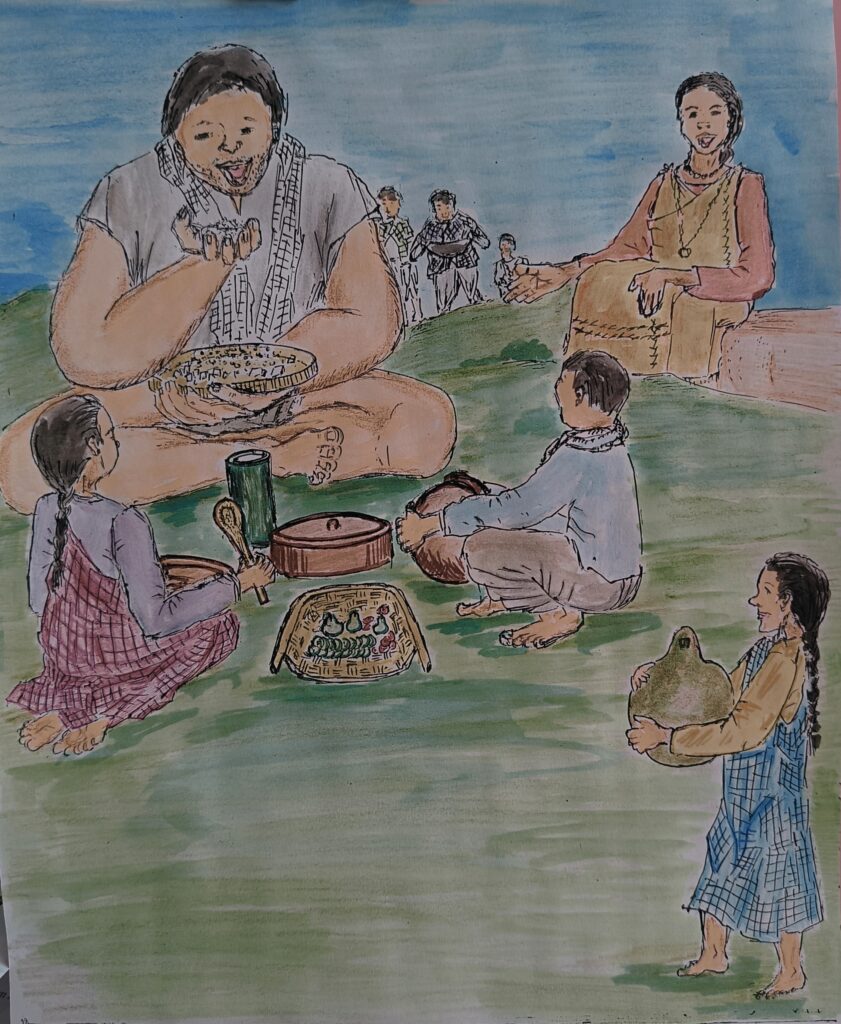

One day Ka Bthuh made a great feast; she sent invitations to many villages far and near, for she wanted it to be as publicly known as possible in order to lure U Ramhah to attend. It was one of his rude habits to go uninvited to feasts and to gobble up all the eatables before the invited guests had been helped.

The day of Ka Bthuh’s feast came and many guests arrived, but before the rice had been dis-tributed there was a loud cry that U Ramhah was marching towards the village. Everybody considered this very annoying, but Ka Bthuh, the hostess, pretended not to be disturbed, and told the people to let the giant eat as much as he liked first, and she would see that they were all helped later on. At this U Ramhah laughed, thinking that she was beginning to be afraid of him, and he helped himself freely to the cooked rice and curry that was at hand. He always ate large mouthfuls, but at feast times he used to put an even greater quantity of rice into his mouth, just to make an impression and a show. Ka Bthuh had anticipated all this, and she stealthily put into the rice some sharp steel blades which the giant swallowed unsuspectingly.

After he had finished eating, U Ramhah left, and Ka Bthuh informed the people of what she had done after he was no longer in sight. They were all impressed by her guile and agreed that it was right to punish someone who had committed so many heinous acts but had escaped punishment because of his immense might. From then on, Ka Bthuh gained popularity and received a lot of accolades.

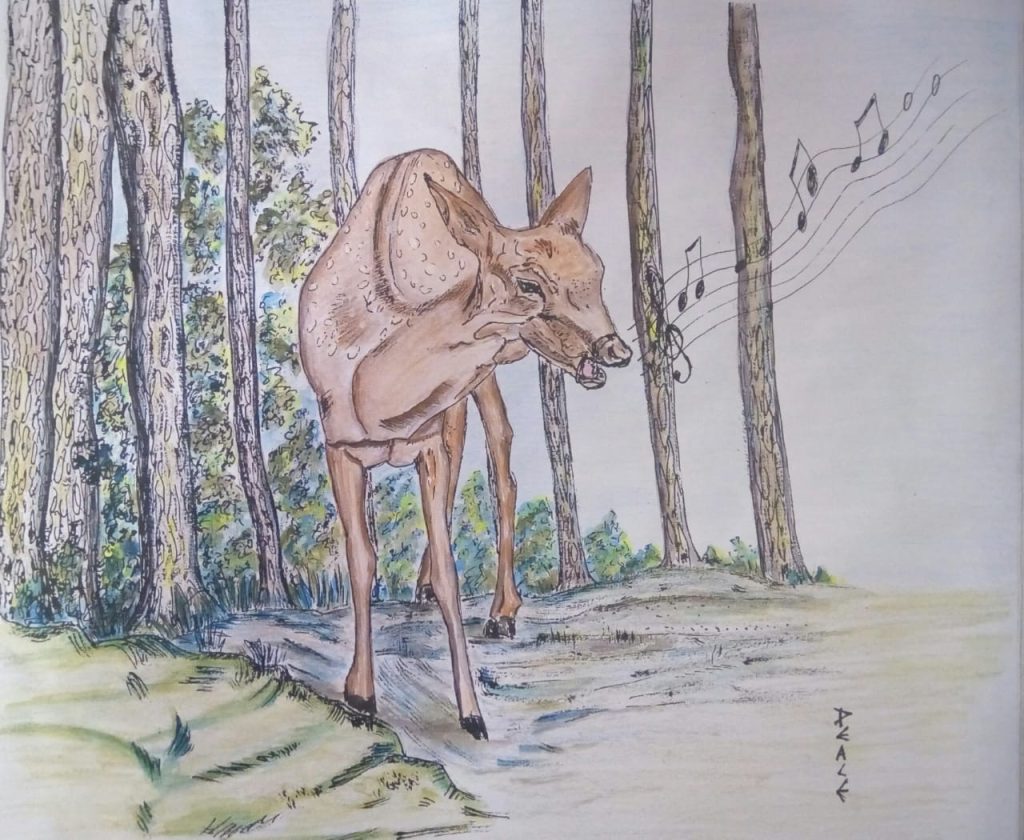

U Ramhah never reached his home from that feast. The sharp blades he had swallowed cut his intestines and he died on the hill-side alone and unattended, as the wild animals die, and there was no one to regret his death.

When the members of his clan heard of his death they came in a great company to perform rites and to cremate his body, but the body was so big that it could not be cremated, and so they decided to leave it till the flesh rotted, and to come again to gather together his bones. After a long time they came to gather the bones, but it was found that there was no urn large enough to contain them, so they piled them together on the hill-side until a large urn could be made.

While the making of the large urn was in pro-gress there arose a great storm, and a wild hurricane blew from the north, which carried away the bleached bones of U Ramhah, and scattered them all over the south borders of the Khasi Hills, where they

remain to this day in the form of lime-rocks, the many winding caves and crevices of which are said to be the cavities in the marrowless bones of the giant. Thus U Ramhah, who injured and plundered the Khasis in his life-time, became the source of inestimable wealth to them after his death.

His name is heard on every hearth, used as a proverb to describe objects of abnormal size or people of abnormal strength.

The illustrator Dr. Peacefully Kharkongor is an Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Women’s College, Shillong. She also has a passion for art.