On 19th December 1929, the Indian National Congress voted for ‘Purna Swaraj’ – total independence from British rule. Several prominent national leaders of the time were at that historic session held in Lahore. From the Khasi hills there was only one gentleman present – U Sib Charan Roy Jaitdkhar Sawian.

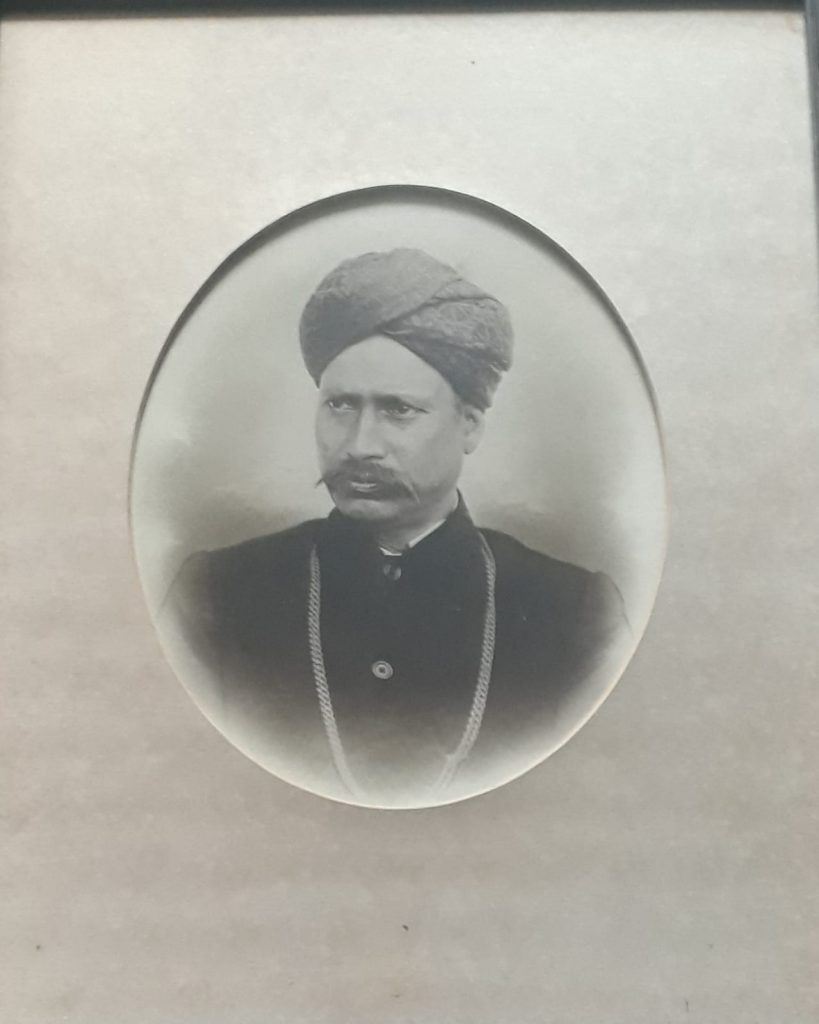

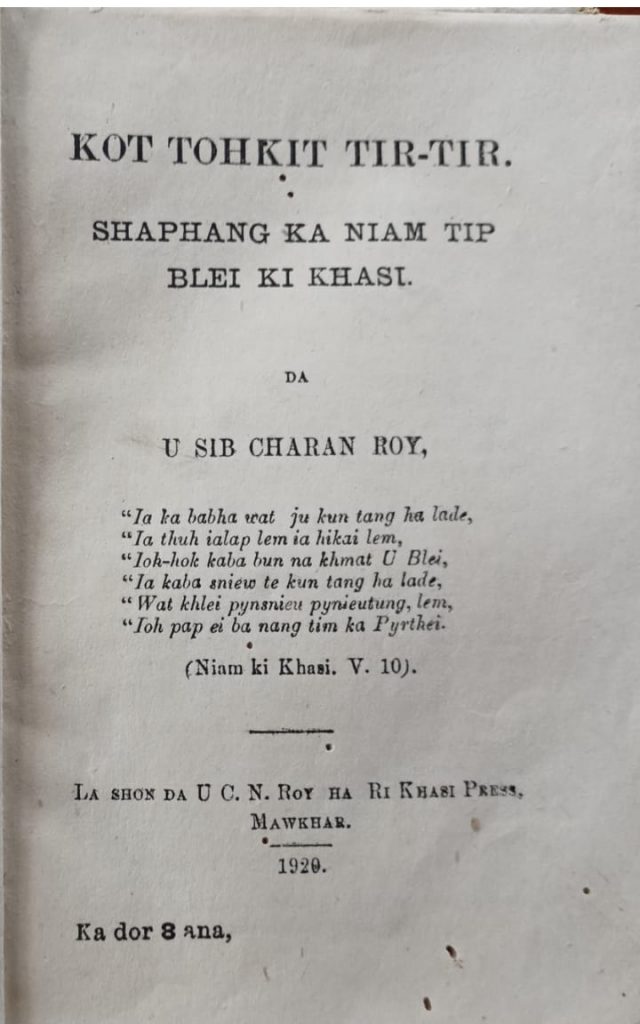

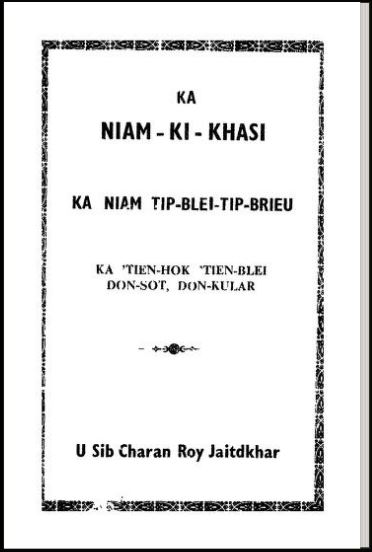

U Sib Charan Roy, born on 4th April 1862 in Sohra, was the eldest son of the legendary Babu Jeebon Roy Mairom. Like his father, he too endeavoured to instill pride in his people, for what was their own, and dedicated his entire life to this cause. He wrote extensively on the philosophy of Niam Khasi (the indigenous faith), translated important Indian religious texts to Khasi, published comparative studies, gave influential lectures in the early formative years of Seng Khasi, wrote patriotic songs that are still sung today, and even battled the agents of the East India Company in a trade war. The famous ‘Shad Suk Mynsiem’ (Dance of the Peaceful Hearts) was initially known as ‘Ka Shad U Sib’ (Sib’s Dance). These are just a few glimpses into his life and contributions.

He was a staunch Khasi who believed in and subscribed to the idea of “India”. For him, there was no conflict between Khasi Nationalism and Indian Nationalism, as he was very clear with the following – the Khasi Way of Life and Worship was an integral part of the great cultural and spiritual heritage of the sub-continent, and British rule was a clear threat to its survival. He fought the British, at the height of their powers, using his intellect and his unshakable belief in himself and his faith.

This clarity led him to support the Swadeshi movement from very early on. He joined the Indian National Congress in 1920. Although he never held an official post at Seng Khasi, he was an icon, and his work greatly helped the organization grow in strength. He propagated the traditional Khasi systems of administration and governance and said that the Khasis were not a conquered people, but he saw how they were rapidly losing their identity. He wanted a Khasi state with its values intact within the “New India”. In his newspaper ‘U Nongphira’ (The Watchman) he shared information and articles about the freedom struggle, created awareness and clarity about the treaties that the Khasi states had signed and was never afraid to expose the propaganda and lies of the colonial machine. The paper was banned in 1915 but he returned with ‘U Nongpynim’ (The Reviver) which was also ultimately banned in 1940.

The British authorities attempted to suppress and silence him multiple times, but he never backed down. He won a very important case maliciously filed against him, known as the Weiking case, where he had been accused of trampling on cemetery grounds on the way to the traditional Khasi dance arena (Lympung Weiking) in Jaiaw, Shillong. This was proven to be false and today the public road that runs down the middle of the hill stands as evidence. Books misinterpreting what he said, to discredit him, are still in publication, an ugly inheritance of the colonial legacy. However, due recognition without bias is also coming to light.

He was a supporter of the non-cooperation movement and adhered to Mahatma Gandhi’s

‘Satyagraha’ -quest into truth. He admired Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose and spoke highly of him, while sections of Khasi society were plotting to protest and pelt stones at the great revolutionary. The poison injected by the British into the psyche of the local populace had sunk in deep. This anti fellow Indian and anti self mentality, tantamounting to self – denigration sadly continues till today. The greatest and most dangerous lie the British and their hounds planted in our minds was that the Khasis had no links with the rest of the country. This sinister divide and ruin policy still weakens us, but I am certain newer generations will not fall prey as easily.

When U Tirot Sing Syiem was battling David Scott and the East India Company, in the early to mid-19th century, the idea of a single independent nation had not fully crystallized. Revolts had spread across the land, but they were largely unconnected. Princely states and small communities began to take up arms on their own. However, by the time U Sib Charan began to write and publish material against the British in ‘U Nongphira’ the idea of an independent and united nation was becoming clearer, although the boundaries would drastically change as demands for a separate Islamic state in the western and the eastern corners of Bharat gained ground. Natural barriers, like rivers and mountain ranges, overnight became the new international borders. Khasis lost vast tracts of land to the newly created East Pakistan, today known as Bangladesh. Communities were split apart on this side of the subcontinent too.

U Sib Charan was confrontational, and fiery at times, but he was always guided by Truth and the search for it. While most Khasis only talk of ‘U Hynñiewtrep’, the Seven Huts, he is one of the few who has ever invoked ‘U Khyndaitrep’, the Nine who remained in the celestial abode of the Divine Creator, U Blei. Not only did he protect the indigenous faith, he also strengthened it. No one can deny that the Khasi identity has been kept intact largely due to efforts of leaders such as him – for the greatest form of preservation is through practice.

He wanted us to grow with and from the power of being part of a deep and vast ocean of spiritual bonds and traditions. It is up to us to derive strength from our similarities, rather than retreat further into the suffocating walls of gloom, desperation, blame and confusion. U Sib Charan believed strongly in the need for reforms, but he was vehemently opposed to outside interference and foreign ideas determining the path forward. His vision was clear – we must progress from our own Roots and understanding of Divinity and Fellow Man.

U Tirot Sing, Kiang Nangbah, U Mit, U Hon, U Dur, U Sib Charan Roy and many more fought not just to protect the land. . They fought for the dignity and soul of the people. Today that soul is growing stronger and clearer, with prideand peace in the garden of our Mother Goddess – Ka Mei Ri India (Bharat Mata). May we and many more continue to bloom in the years to come. Happy 75th year of Independence!

Ïai Minot! Khublei! Jai Hind! ![]()

Hammarsing L Kharhmar, President of ‘Ka Tbian Ki Sur Hara’, a Performing Arts School of Seng Khasi (Kmie).