श्री रामचन्द्र दया निधान,

दयालु हे! जगदीश्वरम्।

तम तोम तारक सुर सुधारक,

सौम्य हे! सर्वेश्वरम्।

मन मणि खचित रवि निकर

सम, छविधाम आप जगत्पते।

सौन्दर्य की उस राशि के

आधार हों सीतापते!

लखि रूप मोहित देव सब

ब्रम्हा, उमा-महेश्वरम्।

श्री रामचन्द्र दया निधान,

दयालु हे! जगदीश्वरम्।

शत् काम लज्जित राम तव

आनन निहारि निहारि के।

सँग नारि सीता रूप छवि,

नव कलित रूप निवारि के।

अस सुयश गावहिं जगत के

सब मनुज हे! अखिलेश्वरम्।

श्री रामचन्द्र दया निधान,

दयालु हे! जगदीश्वरम् ![]()

राजेश तिवारी “विरल”

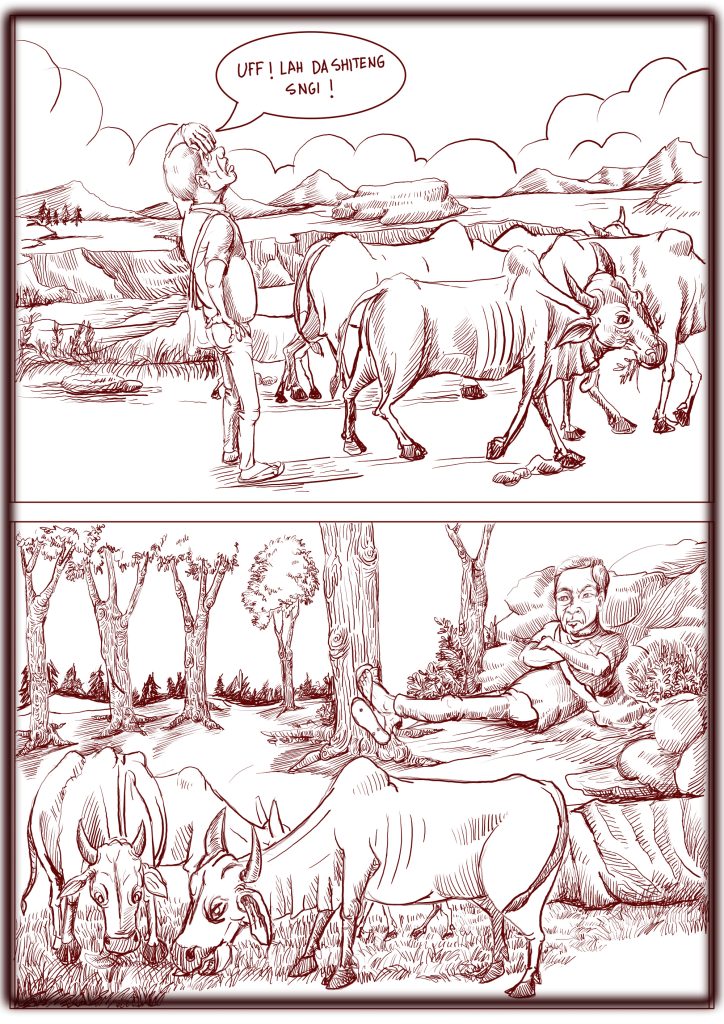

Melban Lyngdoh

The Golden Casket

Bloom of a new light,

Gold - as precious as diamond.

Box full of new mystery.

Open it and you will be swallowed,

Ignore it and you will be chased.

Wonders that were never seen

Time and day will fail to cease.

Dark as the starry sky you see,

Feelings that were never heard or felt to spell

You may see it but fail to be felt

You cannot get out until you answer it,

You cannot hear it until you question it.

Once you answer it day will come

You will forget it all, and it will vanish.

You won’t find it,

You won’t see it.

The secret will be revealed for once and forever,

Days will start again from where it stopped.

Melban Lyngdoh

The Golden Casket

Bloom of a new light,

Gold - as precious as diamond.

Box full of new mystery.

Open it and you will be swallowed,

Ignore it and you will be chased.

Wonders that were never seen

Time and day will fail to cease.

Dark as the starry sky you see,

Feelings that were never heard or felt to spell

You may see it but fail to be felt

You cannot get out until you answer it,

You cannot hear it until you question it.

Once you answer it day will come

You will forget it all, and it will vanish.

You won’t find it,

You won’t see it.

The secret will be revealed for once and forever,

Days will start again from where it stopped.