Long, long ago, on the Khasi Hills, there lived a widow and her only son, a young man of great beauty but who was mentally impeded and was known throughout the community as “U Bieit” (the idiot).

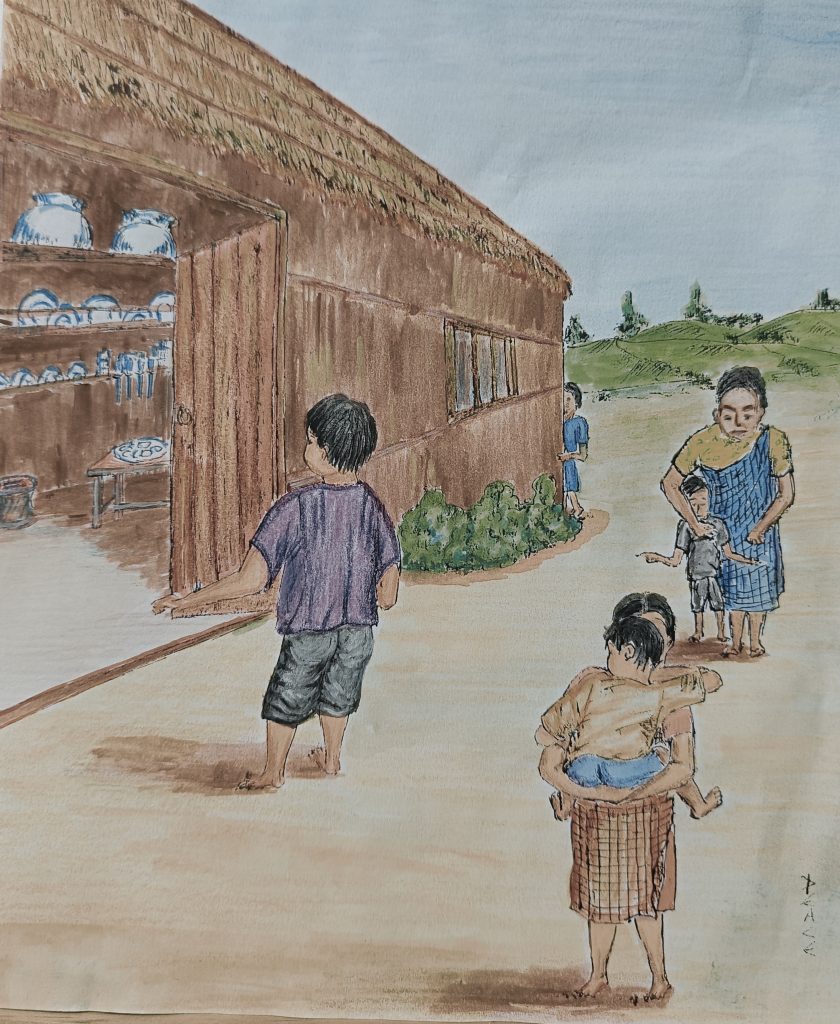

As she was very poor and had none to call her own, she was forced to work every day to provide for herself and her helpless child. So, the son was left to his own ways and roamed freely throughout the hamlet. Naturally, he became a very bothersome child to his neighbors since he frequently broke into their homes to look for food, causing much harm and loss.

U Bieit, like most people of weak intellect, displayed wonderful cunning in some directions, especially in procuring some good thing to eat, and the way he succeeded in duping some of his more shrewd comrades in order to obtain some dainty tit-bits of food was a source of great amusement and merriment. However, there were so many bad situations that people were afraid to leave their homes, and things eventually became so serious that the widow was obliged to leave the hamlet .

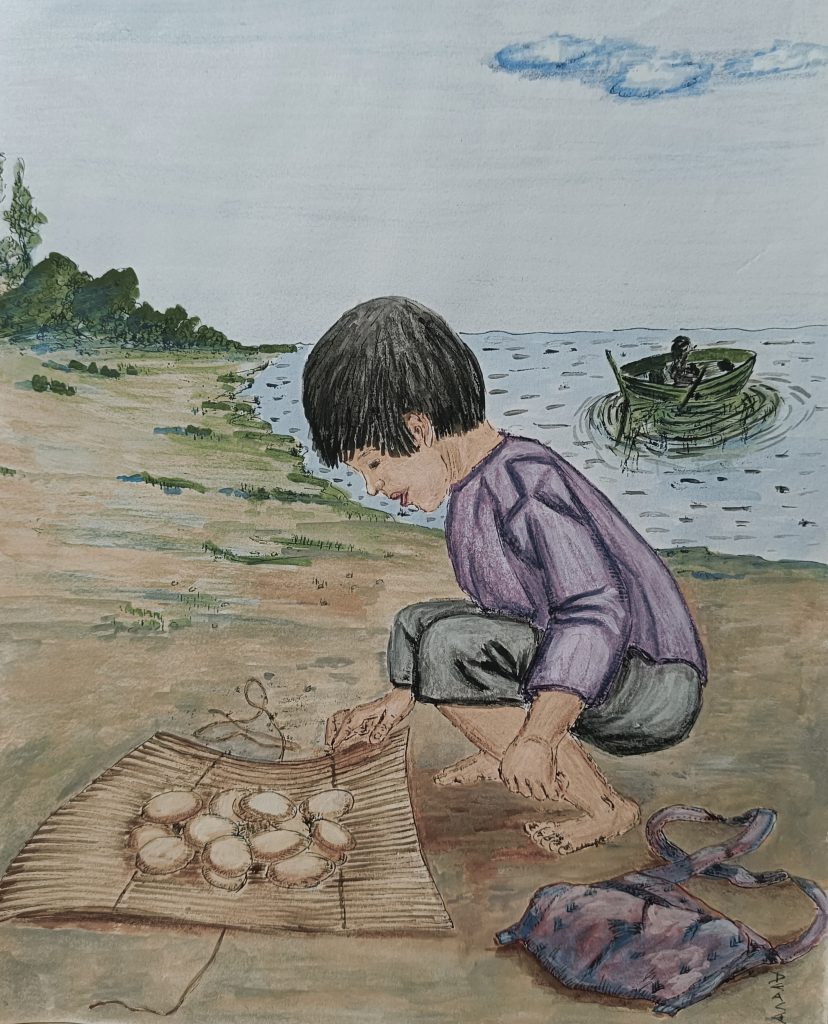

She sought admission into many of the surrounding villages, but the fame of U Bieit had travelled before him and no one was willing to let them dwell in their midst. So in great distress she took him down to the plains, where there was a big river along which many boats used to sail. Here she determined to abandon him, hoping that some of the wealthy merchants who often passed that way might be attracted by his good looks and take him into their company.

She gave him some rice cakes to eat when he should be hungry, and told him to be a good boy and stay by the river-side, and she would bring him more cakes next day. A boy, feeling lonely and uncomfortable in his new surroundings, hides from boats.

A wealthy merchant was returning from a journey when he landed to eat food. The servants were traveling back and forth in the boat while preparing their master’s food. He instructed them to carry his chest of gold nuggets ashore and bury it in the sands near where he sat, as he was worried that some of the servants may tamper with it.

A strong shower fell just as he finished his meal, and the merchant rushed to take refuge in his boat; in his haste, he forgot about the box of gold buried in the sand dunes and the boat sailed away without it.

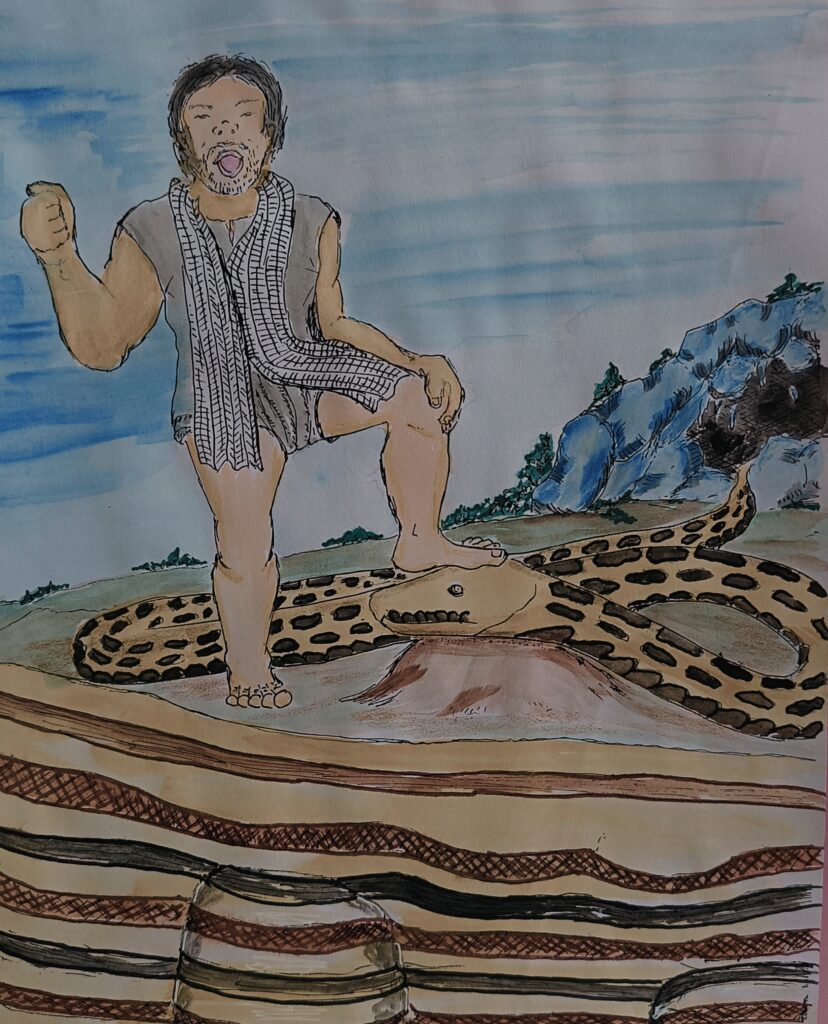

The dumb boy had been watching the activities with keen interest and a desire to enjoy the tempting supper, but fear of the boat with white sails kept him from revealing himself. However, as the boat was out of sight, he emerged from the bush and began unearthing the concealed chest. When he spotted the gold nuggets, he believed they were cakes and tried to eat one by putting it in his mouth. Finding it so difficult, he assumed that it had to be unbaked.

His sad mind immediately flew to his mother, who always baked meals for him at home, and, bearing the heavy chest on his back, he started through the forest to seek her, and his instinct, like that of a homing pigeon, brought him safely to his mother’s door.

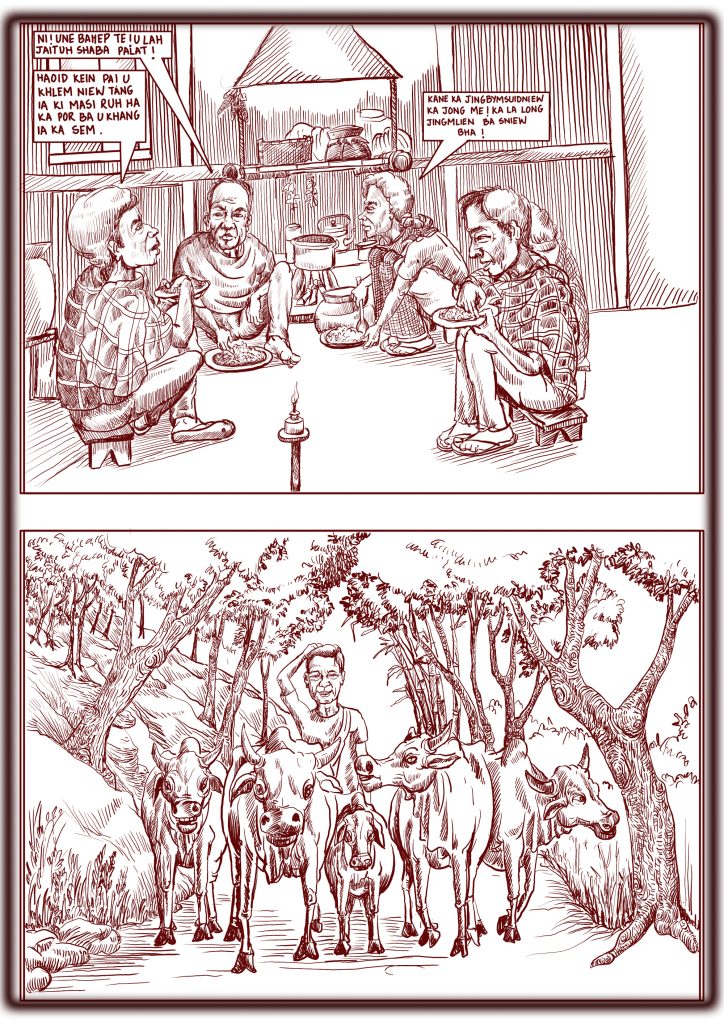

Nobody saw him because it was fairly dark when he arrived at the village. The boy’s mother was grieving for her abandonment and regret for leaving her child. She wished she had money to earn neighbors’ goodwill and live with her son. She heard a shuffling sound at the door and was delighted to find him alive and well.

She was surprised to see him carrying a large chest on his shoulders, and while his silly statements gave no clue into how he had obtained hold of it, her eyes sparkled with excitement when she noticed it was filled of gold nuggets. She let the boy continue to believe they were cakes, and to appease him, she got some rice and baked some savory cakes for him, claiming she was baking the cakes from the chest. He went to bed content and delighted after eating these. Now, the widow had long desired wealth, arguing that she wanted it to provide better comforts for her son, who could not care for himself, but as soon as the gold reached her grasp, her heart was filled with greed. She was not only unwilling to part with any of the nuggets to secure the favor of the people for her son, but she plans to send him abroad to search for more gold, even if he faces danger. She summons him and urges him to return to the riverbank to bring more cakes for her.

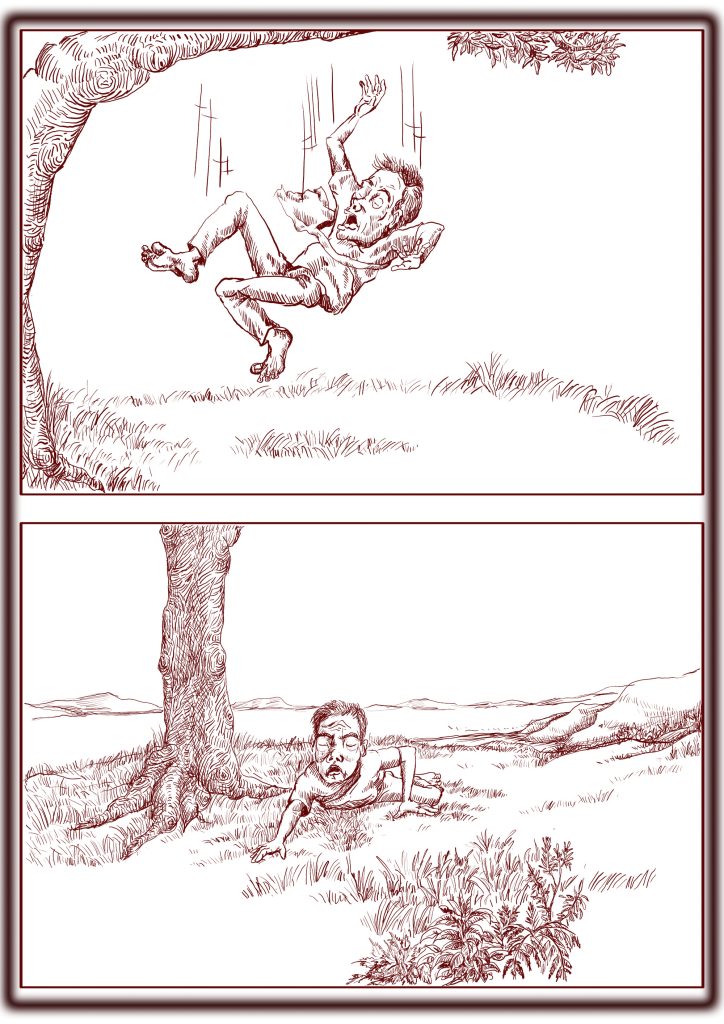

So the child set out on his pointless errand, but soon became lost in the jungle; he couldn’t find the road to the river or his mother’s house, so he wandered around in the deep woods, despairing and hungry, looking for hidden chests and unbaked cakes.

Fairies in a woodland had haunts, but were invisible to humans. They knew about the foolish kid’s sad history and sympathized with his mother’s greed. They decided to take him to the fairies’ country, where he would be safe and receive care from willing hands.

So they said they didn’t have anything else to offer in that location, but if he wanted to accompany them to the country of the fairies beyond the Blue Realm, he could enjoy an abundance of good food and Hyndet cakes. He declared his willingness to leave right away and inquired as to how he should get there. They ordered him to grab their wings, cling tightly, and not speak on the way; so he grabbed the fairies’ wings and the ascent to fairyland began.

As they ascended higher, they saw lovely vistas that delighted the fairies as they passed. They saw the glory of the tallest mountains, and the limitless expanse of forest and river, and the fleeting shadows of the clouds, and the vivid colors of the rainbow, dazzling in their transitory beauty. But the youngster saw none of this since his basic mind was preoccupied with one thought—food. He could no longer suppress his interest as they soared to a great height and the limits of fairyland came into view, and, forgetting everything about the advice not to talk, he enthusiastically questioned the fairies, “Will the Hyndet cakes be big?” He lost his grip on the fairies as soon as he said the words he lost his hold on the fairies’ wings and, falling to the earth with great velocity, he died.

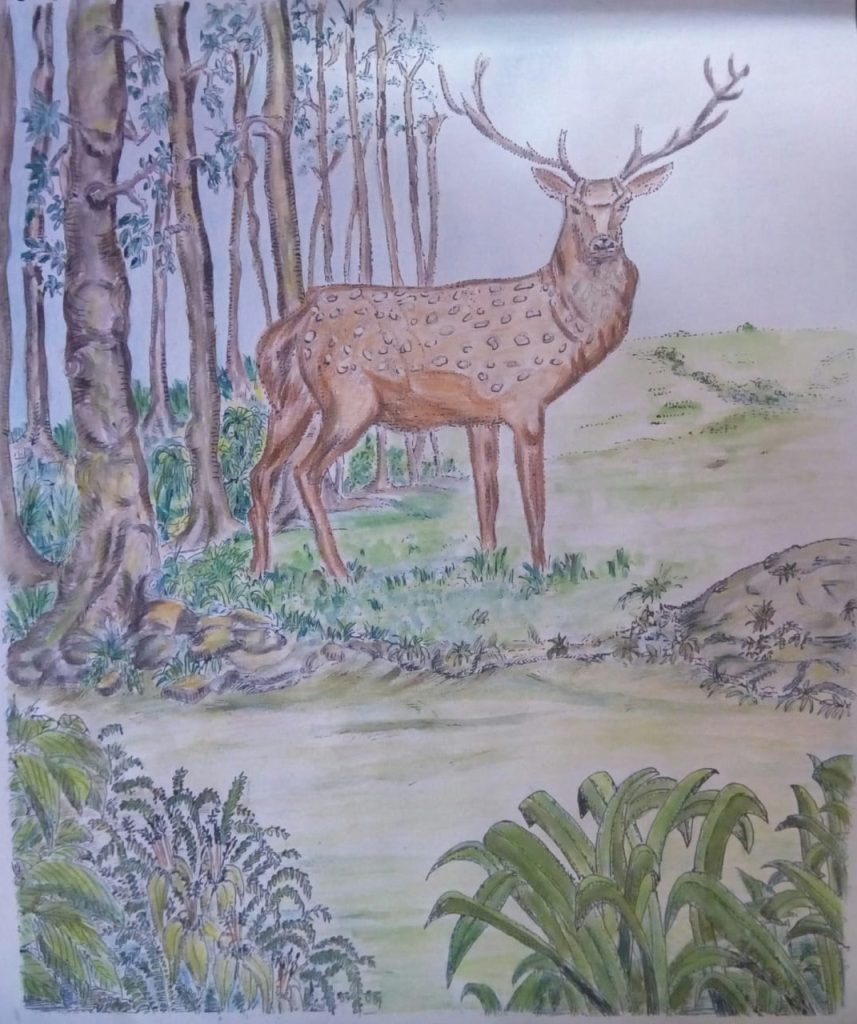

Once upon a time there lived with its dam on the Plains of Sylhet a young deer whose fame has come down through the ages in Khasi folk-lore. The story of the Stag Lapalang, as he was called, continues to fascinate generation after generation of Khasi youths, and the merry cowboys, as they sit in groups on the wild hill-sides watching their flocks, love to relate the oft-told tale and to describe what they consider the most famous hunt in history.The Stag Lapalang was the noblest young animal of his race that had ever been seen in the forest and was the pride of his mother’s heart. She watched over him with a love not surpassed by the love of a human mother, keeping him jealously at her side, guarding him from all harm.

As he grew older the young stag, conscious of his own matchless grace and splendid strength, began to feel dissatisfied with the narrow confines and limited scope of the forest where they lived and to weary of his mother’s constant warnings and counsels. He longed to explore the world and to put his mettle to the test.

His mother had been very indulgent to him all his life and had allowed him to have much of his own way, so there was no restraining him when he expressed his determination to go up to the Khasi Hills to seek begonia leaves to eat. His mother entreated and warned him, but all in vain. He insisted on going, and she watched him sorrowfully as with stately strides and lifted head he went away from his forest home.

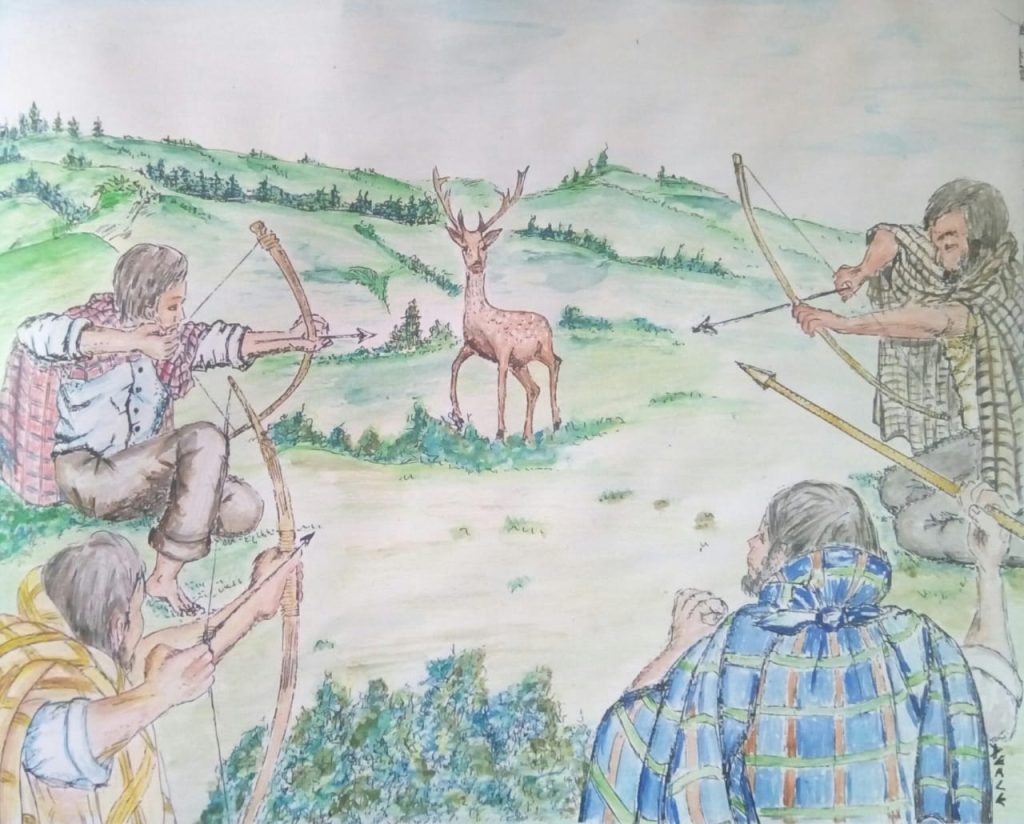

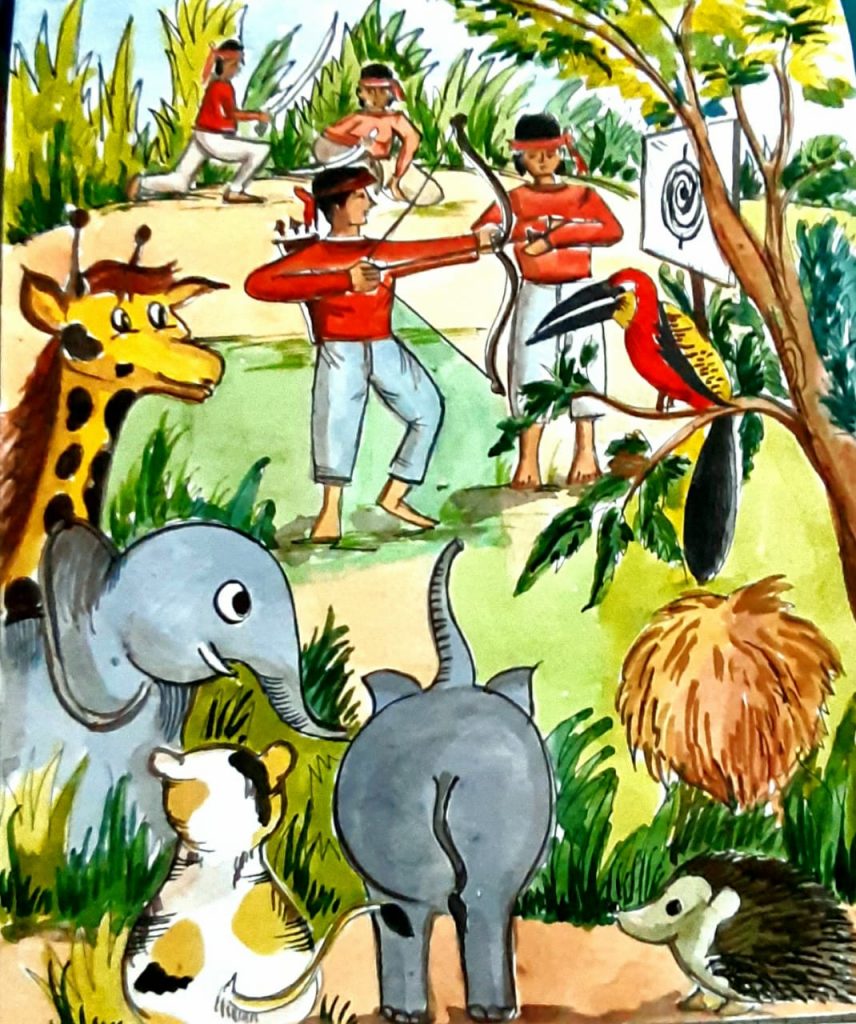

Matters went well with the Stag Lapalang at first; he found on the hills plenty of begonia leaves and delicious grass to eat, and he revelled in the freedom of the cool heights. But one day he was seen by some village boys, who immediately gave the alarm, and men soon hurried to the chase: the hunting-cry rang from village to village and echoed from crag to crag. The hunting instincts of the Khasis were roused and men poured forth from every village and hamlet.

Oxen were forgotten at the plough; loads were thrown down and scattered; nothing mattered for the moment but the wild exciting chase over hill and valley. Louder sounded the hunting cry, farther it echoed from crag to crag, still wilder grew the chase. From hill to hill and from glen to glen came the hunters, with arrows and spears and staves and swords, hot in pursuit of the Stag Lapalang.

He was swift, he was young, he was strong—for days he eluded his pursuers and kept them at bay; but he was only one unarmed creature against a thousand armed men. His fall was inevitable, and one day on the slopes of the Shillong mountain he was surrounded, and after a brave and desperate struggle for his life, the noble young animal died with a thousand arrows quivering in his body.

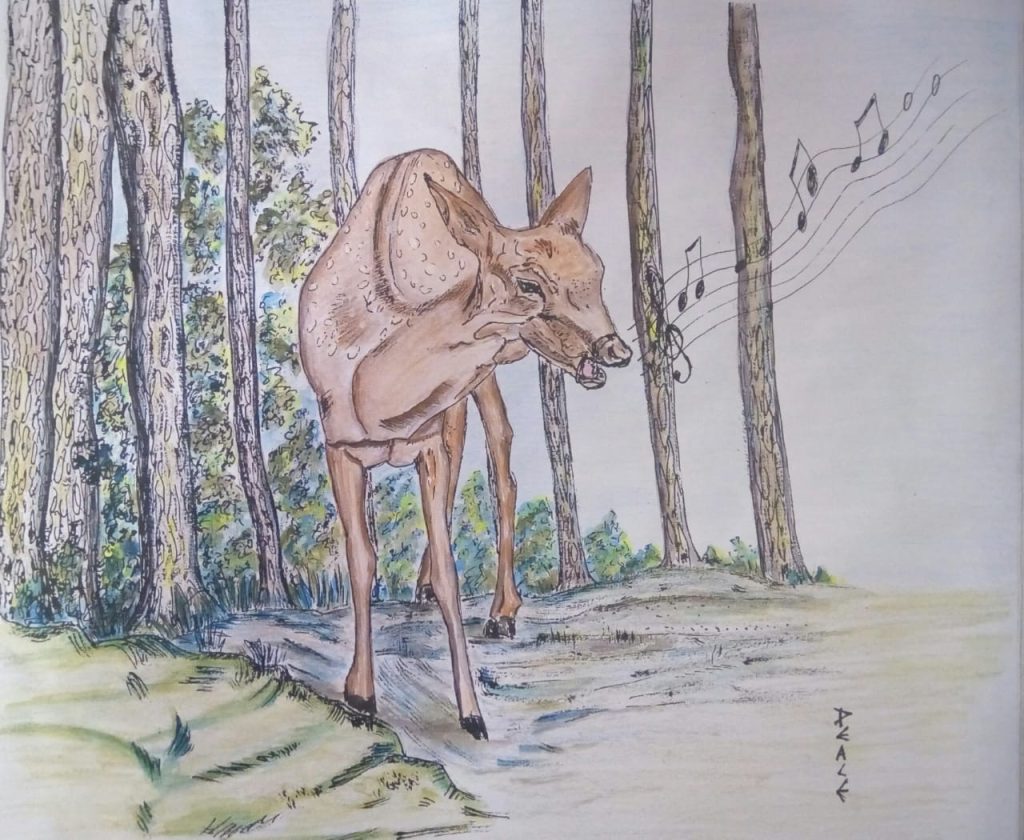

The lonely mother on the Plains of Sylhet became uneasy at the delay of the return of the Stag Lapalang, and when she heard the echoes of the hunting-cry from the hills her anxiety became more than she could endure. Full of dread misgivings, she set out in quest of her wanderer, but when she reached the Khasi hills, she was told that he had been hunted to death on the slopes of Shillong, and the news broke her heart.

Staggering under the weight of her sorrow, she traversed the rugged paths through the wildwoods, seeking her dead offspring, and as she went her loud heartrending cries were heard throughout the country, arresting every ear. Women, sitting on their hearths, heard it and swooned from the pain of it, and the children hid their faces in dismay; men at work in the fields heard it and bowed their heads and writhed with the anguish of it. Not a shout was raised for a signal at sight of that stricken mother, not a hand was lifted to molest her, and when the huntsmen on the slopes of Shillong heard that bitter cry their shouts of triumph froze upon their lips, and they broke their arrows in shivers.

Never before was heard a lamentation so mournful, so plaintive, so full of sorrow and anguish and misery, as the lament of the mother of the Stag Lapalang as she sought him in death on the slopes of Shillong. The Ancient Khasis were so impressed by this demonstration of deep love and devotion that they felt their own manner of mourning for their dead to be very inferior and orderless, and without meaning. Henceforth they resolved that they also would mourn their departed ones in this devotional way, and many of the formulas used in Khasi lamentations in the present day are those attributed to the mother of the Stag Lapalang when she found him hunted to death on the slopes of Shillong hundreds and hundreds of years ago![]()

Dr. Peacefully Kharkongor is an Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Women’s College, Shillong. She also has a passion for art.

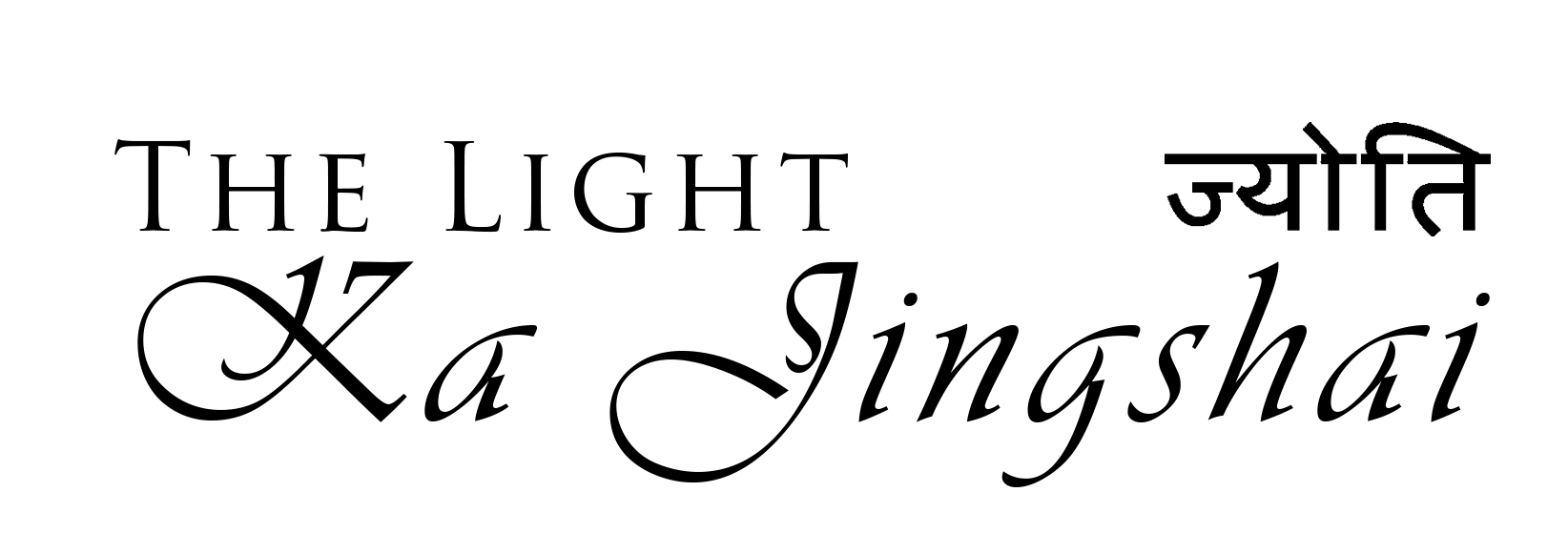

Once there lived a young cowherd, in the rolling lush green hills of the Khasis. As in olden days, and even in today’s village life, every member of a family are allotted certain duties to perform on a daily basis2.

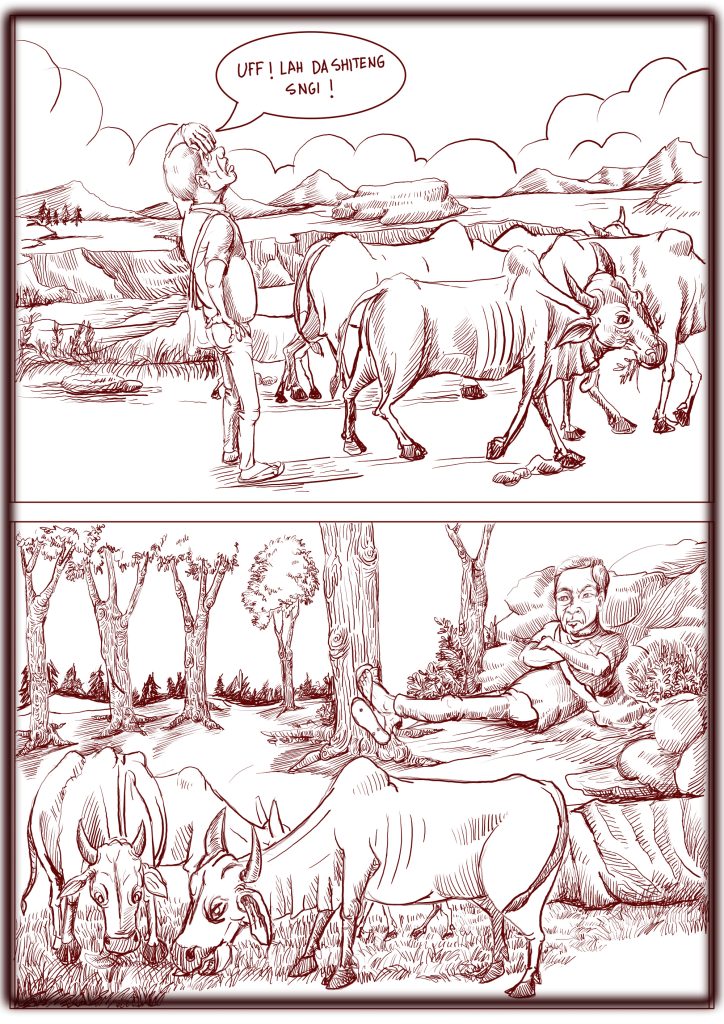

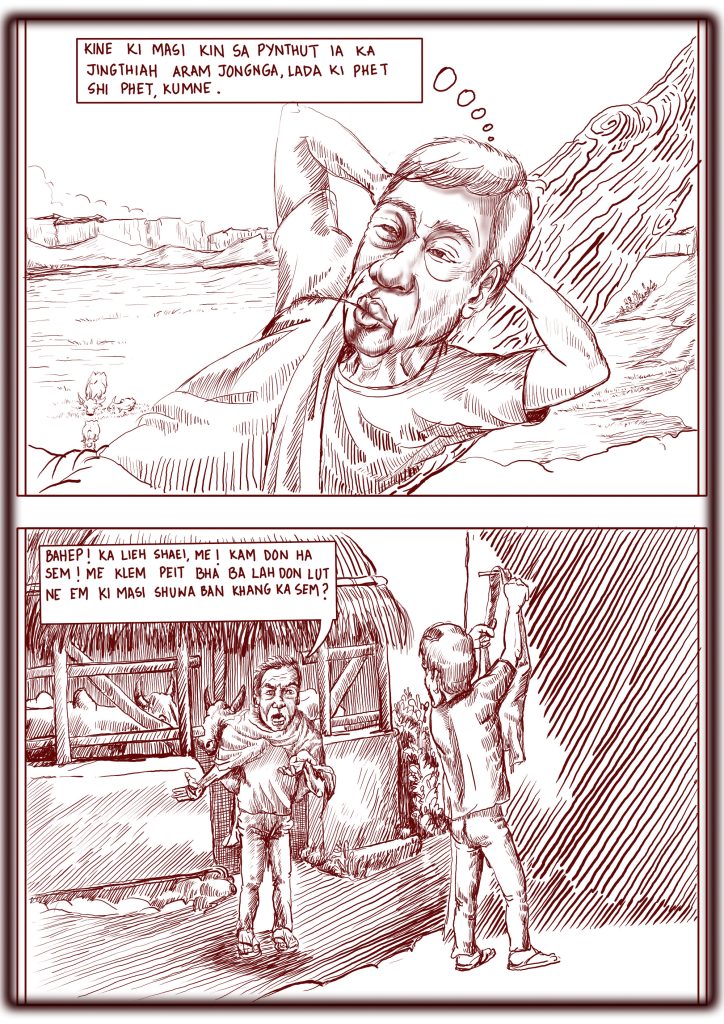

U Bahep (a nickname given to the cowherd by his family and known to everyone in the village) was a very lazy young man. Every day by sunrise, there would be hustle and bustle in the village, as most of the people would be up and about doing their daily chores.

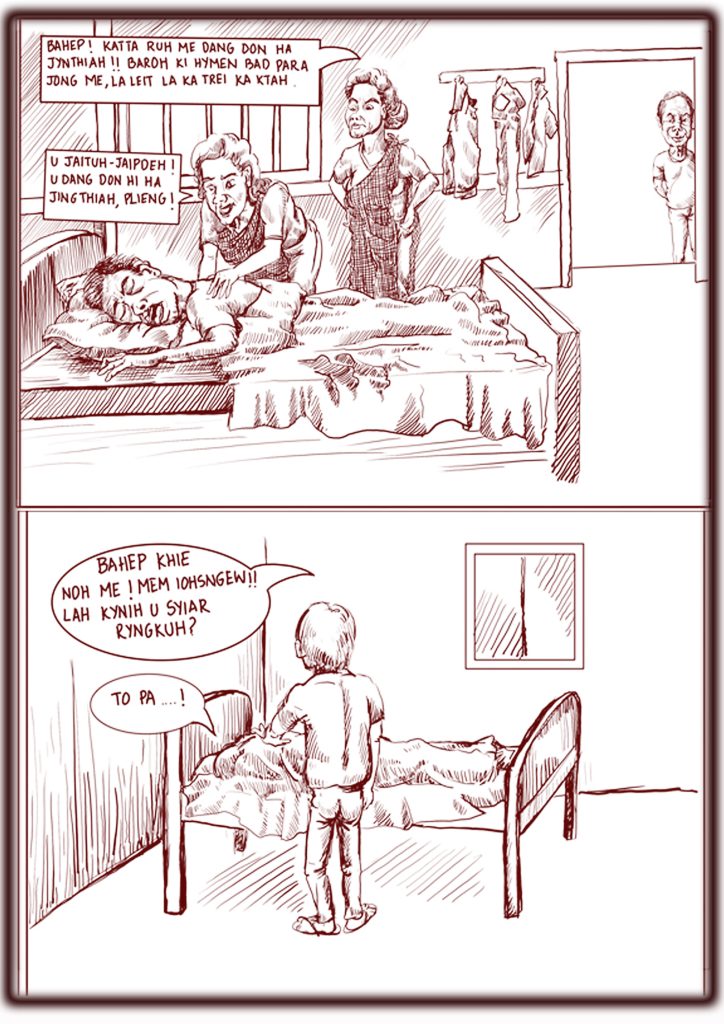

All, except for Bahep; who even after being roused several times by the shrill voices of his mother and sisters; though awake, would still laze in bed. He was always the last person to get out of bed, and also the last one to start his daily chores and this was known to everyone in the village.

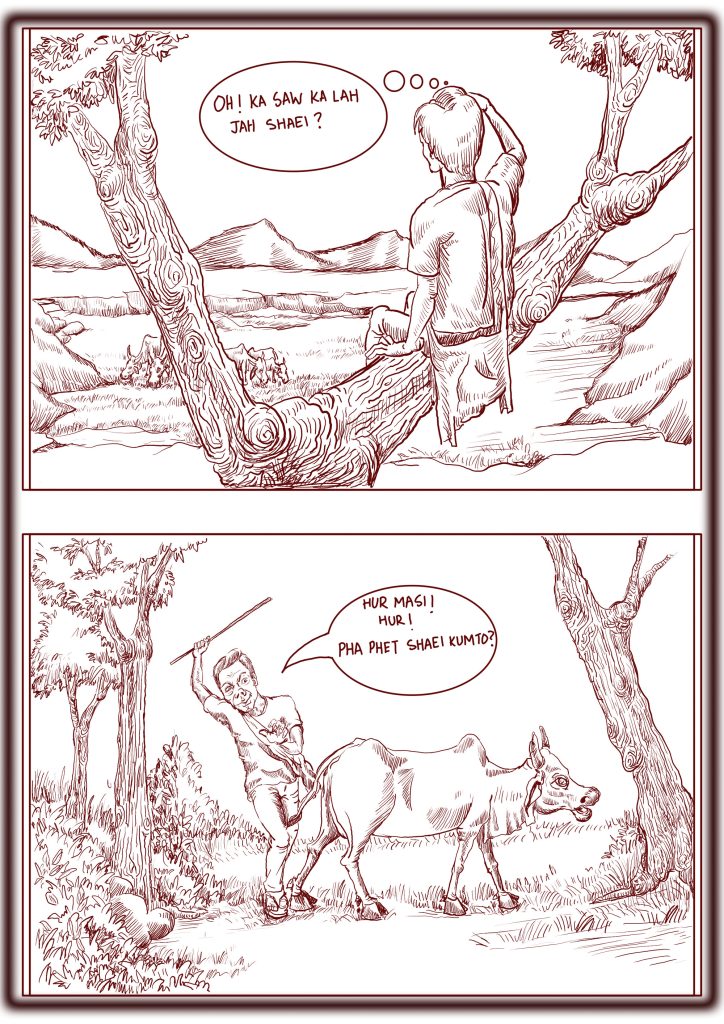

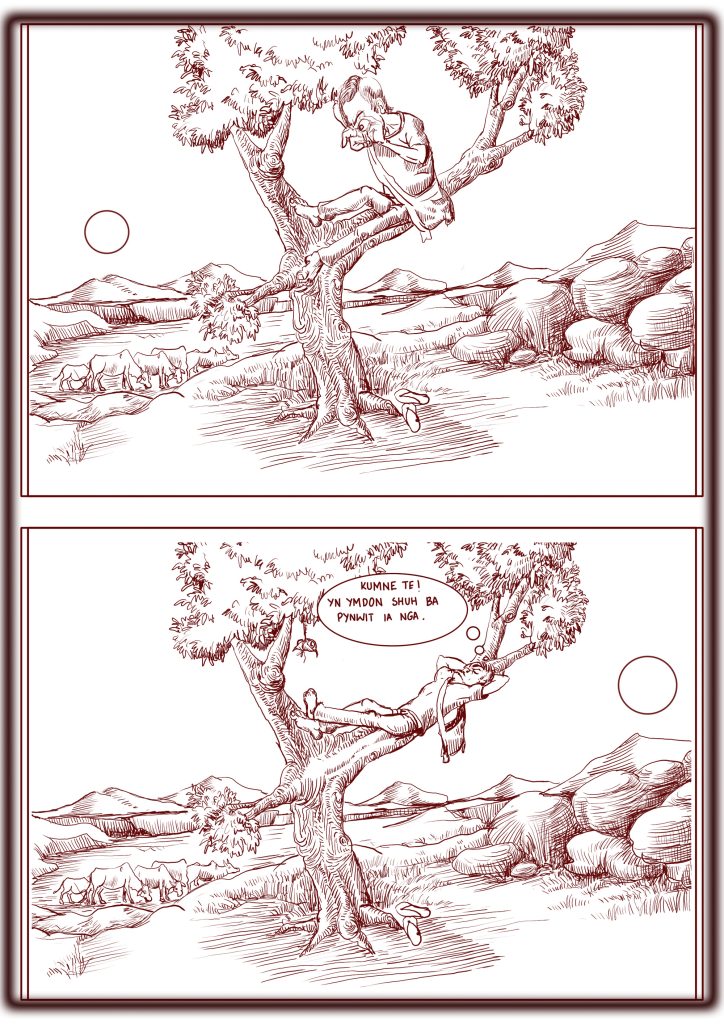

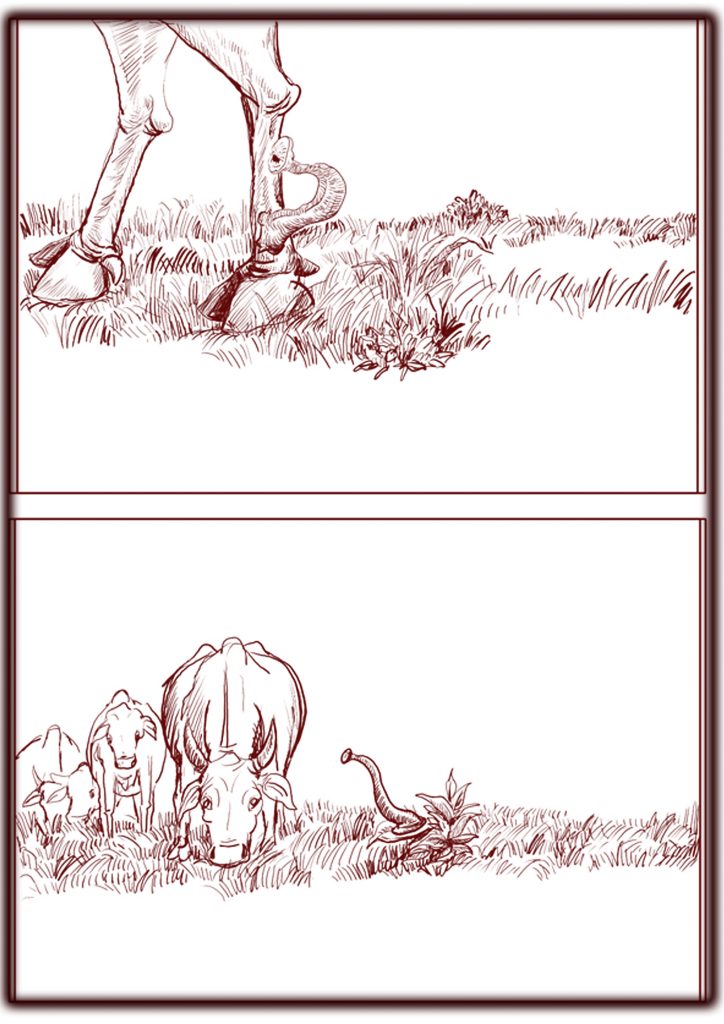

It would almost be noon, by the time he took his cattle out to graze in the open pastures. Upon reaching, he would let his cattle loose and climb onto a nearby tree branch to have a bird’s eye view of his cattle grazing.

On more than one occasion, he would have to climb down the tree, to look for a cow that had strayed, and he knew he would be held accountable for any missing cow, which bothered him, as he intended to relax and nap on a tree branch without any disturbance.

He pondered over the same, and came up with a solution that if one did not see a thing happen, then one cannot be held responsible for such incidents. Therefore, to maintain a clear conscience, he devised a way to remove his eyeballs from his eye sockets, which he then wrapped in a leaf, and tied with a length of vine and hung them on a nearby branch. This became a daily habit of his, and at dusk, satisfied with his nap would reach for his eyeballs and put them back in his eye sockets. He would then round up his cattle, and drive them back to their shed. One many occasions, when one or more of the cattle would be missing, and he would be scolded by his father, Bahep would delegate the task of looking for the lost cow(s) to his younger brothers and cousins by bullying and threatening them.

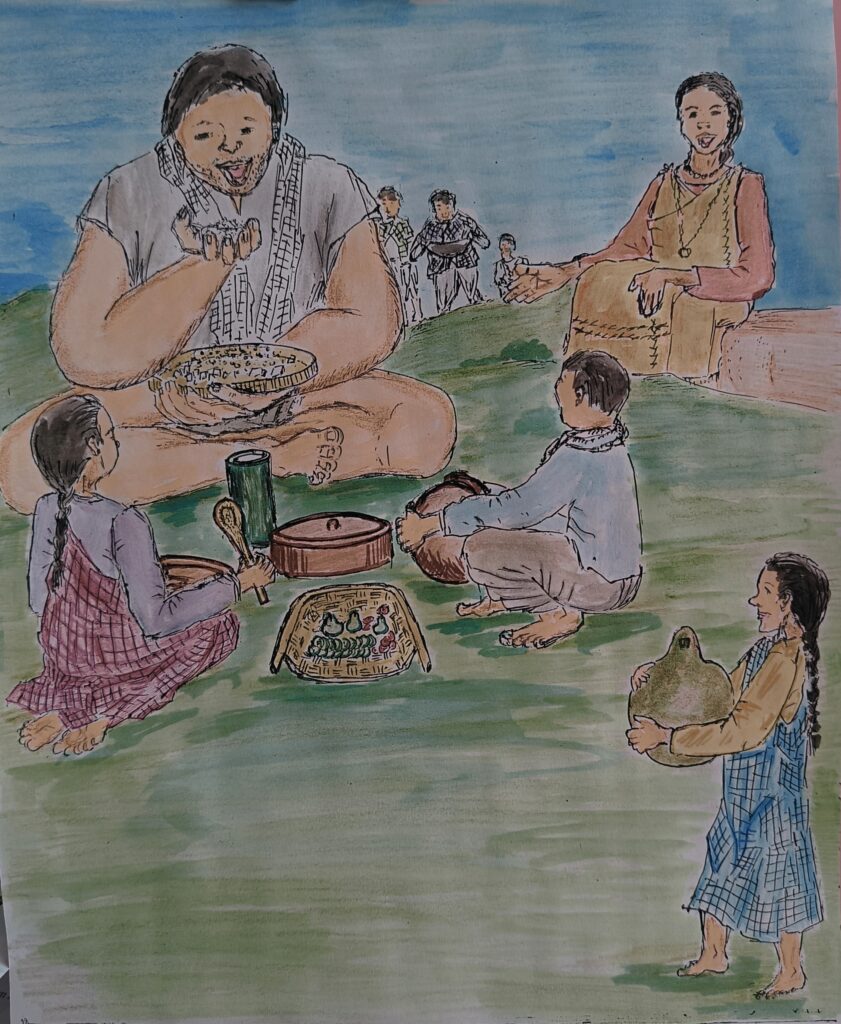

One afternoon, ‘U Khlieng’ a kite, perched upon the tree Bahep was napping on, looking for insects to feed on, and spotted the eyeballs in the leaf hanging by the vines on one of the branches. Thinking it was some sort insect; the kite picked them up and flew away. When the dusk set in, U Bahep started to grope in the dark for the vines in which he had strung his eyeballs in, but alas!! it was all in vain. Bahep, frantic, fell off the tree on the ground below, and desperately kept on groping around in the hope of finding his missing eyeballs.

Days, nights, weeks and months passed, and his search continued amongst the pastures and the trees he used to frequent. In this search he strayed and was lost in the middle of nowhere. As time passed, he shrunk in size little by little, as he had little or no food to sustain him, and this took a heavy toll on his entire being, which to adapt, evolved and metamorphosised into a leech without eyes and only a mouth, which he used, to attach himself to the cows to feed on their blood when they grazed in the pastures.

Moral of the story: Don’t be lazy! The cowherd was a strong, healthy and able bodied young man, but due to his laziness he shunned all his responsibilities and was completely careless. His irresponsible and irrational behavior reduced his whole being from a full-fledged human who once herded cows out to graze on the green pastures, to being a leech, which clings to the grasses and latches onto the same cows to feed himself. According to Khasi Folklore this is how a leech, one of Nature’s Creations, came into being.

Illustrations: Dr Bhogtoram Mawroh

In the happy olden days, when the animals lived together at peace in the forest, they used to hold fairs and markets after the manner of mankind. The most important fair of all was called “Ka Iew Luri Lura”(the Fair of Luri Lura), which was held at stated intervals in the Bhoi (forest) country. Thither gathered all the animals, each one bringing some article of merchandise, according to the decree which demanded that every animal that came to the fair should bring something to sell. No matter whether he was young or old, rich or poor, no one was to come empty-handed, for they wanted to enhance the popularity of the market. U Khla, the tiger, was appointed governor of the fair.

Man was excluded from these fairs as he was looked upon as an enemy. He used to hunt the animals with his bow and arrows, so they had ceased to fraternise with him and kept out of his way. But one day the dog left his own kindred in the jungle, and became the attendant of Man. The following story tells how that came to pass.

One day U Ksew, the dog, walked abroad in search of goods to sell at the fair. The other animals were thrifty and industrious, they worked to produce their merchandise, but the dog, being of an indolent nature, did not like to work, though he was very desirous to go to the fair. So, to avoid the censure of his neighbours and the punishment of the governor of the fair, he set out in search of something he could get without much labour to himself. He trudged about the country all day, inquiring at many villages, but when evening-time came he had not succeeded in purchasing any suitable goods, and he began to fear that he would have to forgo the pleasure of attending the fair after all.

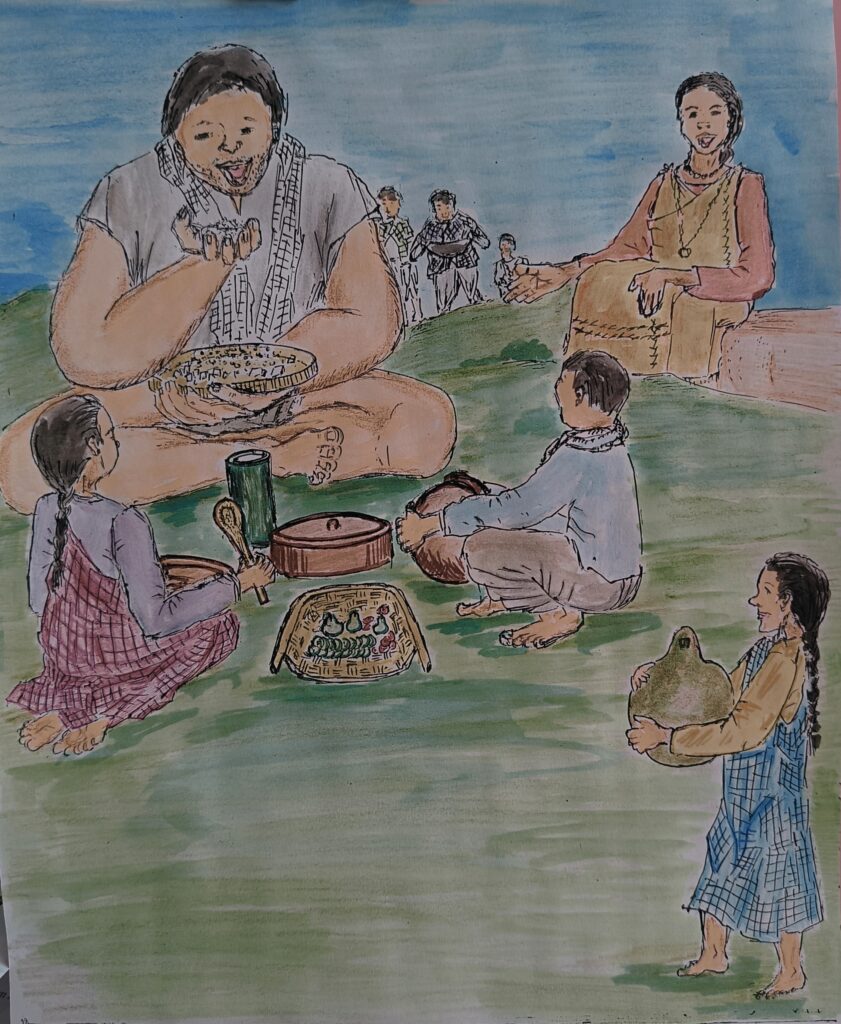

Just as the sun was setting he found himself on the outskirts of Saddew village, on the slopes of the Shillong Mountain, and as he sniffed the air he became aware of a strong and peculiar odour, which he guessed came from some cooked food. Being hungry after his long tramp, he pushed his way forward, following the scent till he came to a house right in the middle of the village, where he saw the family at dinner, which he noticed they were eating with evident relish. The dinner consisted of fermented Khasi beans, known as ktung rymbai, from which the strong smell emanated.

The Khasis are naturally a very cordial and hospitable people, and when the good wife of the house saw the dog standing outside looking wistfully at them she invited him to partake of what food there was left in the pot. U Ksew thankfully accepted, and by reason of his great hunger he ate heartily, regardless of the strange flavour and smell of the food, and he considered the ktung rymbai very palatable.

It dawned on him that here, quite by accident, he had found a novel and marketable produce to take to the fair; and it happened that the kindly family who had entertained him had a quantity of the stuff for sale which they kept in earthen jars, sealed with clay to retain its flavour. After a little palaver according to custom, a bargain was struck, and U Ksew became the owner of one good-sized jar of ktung rymbai, which he cheerfully took on his back. He made his way across the hills to Luri Lura fair, chuckling to himself as he anticipated the sensation he would create and the profits he would gain, and the praise he would win for being so enterprising.

On the way he encountered many of the animals who like himself were all going to Luri Lura, and carrying merchandise on their backs to sell at the fair: to them U Ksew boasted of the wonderful food he had discovered and was bringing with him to the market in the earthen jar under the clay seal. He talked so much about it that the contents of the earthen jar became the general topic of conversation between the animals, for never had such an article been known at Luri Lura.

When he arrived at the fair the dog walked in with great consequence, and installed himself and his earthen jar in the most central place with much clatter and ostentation. Then he began to shout at the top of his voice, “Come and buy my good food, ”and what with his boastings on the road and the noise he made at the fair, a very large company gathered round him, stretching their necks to have a glimpse at the strange-looking jar, and burning with curiosity to see the much-advertised contents.

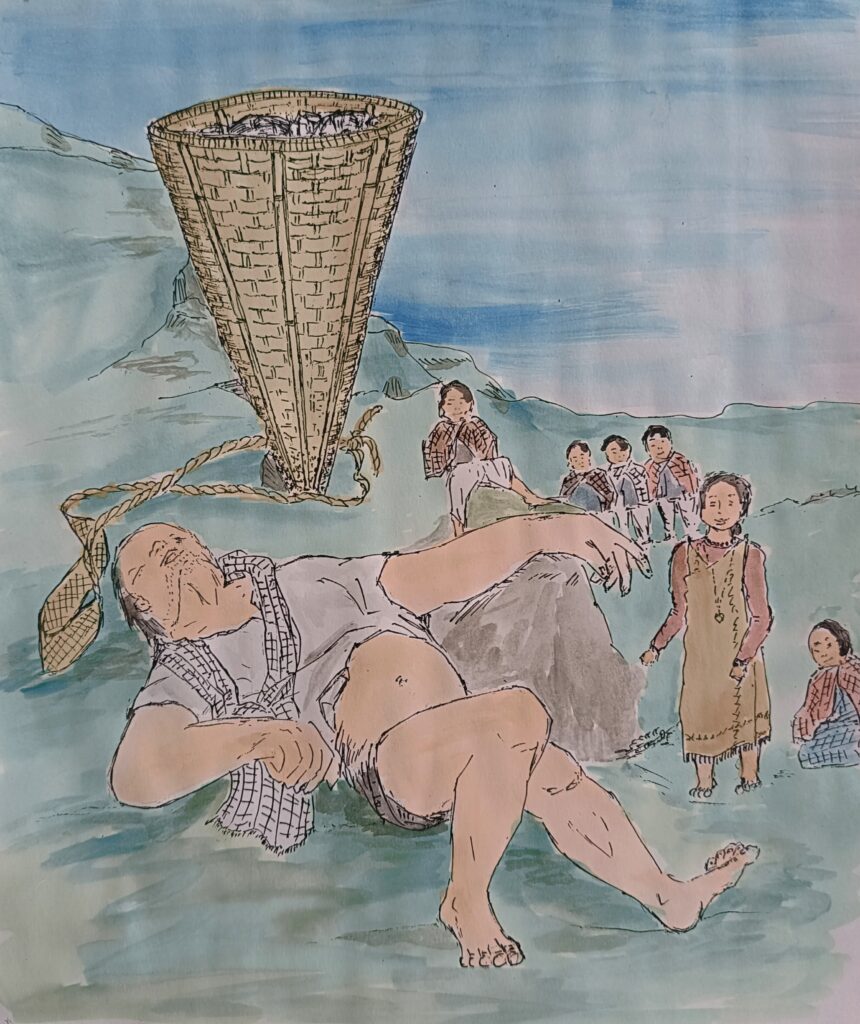

U Ksew, with great importance, proceeded to uncover the jar; but as soon as he broke the clay seal a puff of the most unsavoury and fœtid odour issued forth and drove all the animals scrambling to a safe distance, much to the dog’s discomfiture and the merriment of the crowd. They hooted and jeered, and made all sorts of disparaging remarks till U Ksew felt himself covered with shame.

The stag pushed forward, and to show his disdain he contemptuously kicked the earthen jar till it broke. This increased the laughter and the jeering, and more of the animals came forward, and they began to trample the ktung rymbai in the mud, taking no notice of the protestations of U Ksew, who felt himself very unjustly treated.

He went to U Khla, the governor of the fair, to ask for redress, but here again he was met with ridicule and scorn, and told that he deserved all the treatment he had received for filling the market-place with such a stench.

At last U Ksew’s patience wore out, he grew snappish and angry, and with loud barks and snarls he began to curse the animals with many curses, threatening to be avenged upon them all some day. At the time no one heeded his curses and threats, for the dog was but a contemptible animal in their estimation, and it was not thought possible for him to work much harm. Yet even on that day a part of his curse came true, for the animals found to their dismay that the smell of the ktung rymbai clung to their paws and their hoofs, and could not be obliterated; so the laughter was not all on their side.

Humiliated and angry, the dog determined to leave the fair and the forest and his own tribe, and to seek more congenial surroundings; so he went away from Luri Lura, never to return, and came once more to Saddew village, to the house of the family from whom he had bought the offending food. When the master of the house heard the story of the ill-treatment he had suffered from the animals, he pitied U Ksew, and he also considered that the insults touched himself as well as the dog, inasmuch as it was he who had prepared and sold the ktung rymbai. So he spoke consolingly to U Ksew and patted his head and told him to remain in the village with him, and that he would protect him and help him to avenge his wrongs upon the animals.

After the coming of the dog, Man became a very successful hunter, for the dog, who always accompanied him when he went out to hunt, was able to follow the trail of the animals by the smell of the ktung rymbai, which adhered to their feet. Thus the animals lived to rue the day when they played their foolish pranks on U Ksew and his earthen jar at the fair of Luri Lura.

Man, having other occupations, could not always go abroad to the jungle to hunt; so in order to secure a supply of meat for himself during the non-hunting seasons he tamed pigs and kept them at hand in the village. When the dog came he shared the dwelling and the meals of the pig, U Sniang; they spent their days in idleness, living on the bounty of Man.

One evening, as Man was returning from his field, tired with the day’s toil, he noticed the two idle animals and he said to himself—“It is very foolish of me to do all the hard work myself while these two well-fed creatures are lying idle. They ought to take a turn at doing some work for their food.”

The following morning Man commanded the two animals to go to the field to plough in his stead. When they arrived there U Sniang, in obedience to his master’s orders, began to dig with his snout, and by nightfall had managed to furrow quite a large patch of the field; but U Ksew, according to his indolent habits, did no work at all. He lay in the shade all day, or amused himself by snapping at the flies. In the evening, when it was time to go home, he would start running backwards and forwards over the furrows, much to the annoyance of the pig.

The same thing happened for many days in succession, till the patience of the pig was exhausted, and on their return from the field one evening he went and informed their master of the conduct of the dog, how he was idling the whole day and leaving all the work for him to do.

The master was loth to believe these charges against U Ksew, whom he had found such an active and willing helper in the chase: he therefore determined to go and examine the field. When he came there he found only a few of the footprints of the pig, while those of the dog were all over the furrows. He at once concluded that U Sniang had falsely charged his friend, and he was exceedingly wroth with him.

When he came home, Man called the two animals to him, and he spoke very angrily to U Sniang, and told him that henceforth he would have to live in a little sty by himself, and to eat only the refuse from Man’s table and other common food, as a punishment for making false charges against his friend; but the dog would be privileged to live in the house with his master, and to share the food of his master’s family.

Thus it was that the dog came to live with Man.

Bhogtoram Mawroh is a freelance Cartoonist and Artist. He works as Senior Associate, Research and Knowledge Management at North East Slow Food and Agrobiodiversity Society

Man was excluded from these fairs as he was looked upon as an enemy. He used to hunt the animals with his bow and arrows, so they had ceased to fraternise with him and kept out of his way. But one day the dog left his own kindred in the jungle, and became the attendant of Man. The following story tells how that came to pass.

One day U Ksew, the dog, walked abroad in search of goods to sell at the fair. The other animals were thrifty and industrious, they worked to produce their merchandise, but the dog, being of an indolent nature, did not like to work, though he was very desirous to go to the fair. So, to avoid the censure of his neighbours and the punishment of the governor of the fair, he set out in search of something he could get without much labour to himself. He trudged about the country all day,

inquiring at many villages, but when evening-time came he had not succeeded in purchasing any suitable goods, and he began to fear that he would have to forgo the pleasure of attending the fair after all.

Just as the sun was setting he found himself on the outskirts of Saddew village, on the slopes of the Shillong Mountain, and as he sniffed the air he became aware of a strong and peculiar odour, which he guessed came from some cooked food. Being hungry after his long tramp, he pushed his way forward, following the scent till he came to a house right in the middle of the village, where he saw the family at dinner, which he noticed they were eating with evident relish. The dinner consisted of fermented Khasi beans, known as ktung rymbai, from which the strong smell emanated.

The Khasis are naturally a very cordial and hospitable people, and when the good wife of the house saw the dog standing outside looking

wistfully at them she invited him to partake of what food there was left in the pot. U Ksew thankfully accepted, and by reason of his great hunger he ate heartily, regardless of the strange flavour and smell of the food, and he considered the ktung rymbai very palatable.

It dawned on him that here, quite by accident, he had found a novel and marketable produce to take to the fair; and it happened that the kindly family who had entertained him had a quantity of the stuff for sale which they kept in earthen jars, sealed with clay to retain its flavour. After a little palaver according to custom, a bargain was struck, and U Ksew became the owner of one good-sized jar of ktung rymbai, which he cheerfully took on his back. He made his way across the hills to Luri Lura fair, chuckling to himself as he anticipated the sensation he would create and the profits he would gain, and the praise he would win for being so enterprising.

On the way he encountered many of the animals who like himself were all going to Luri Lura, and

carrying merchandise on their backs to sell at the fair: to them U Ksew boasted of the wonderful food he had discovered and was bringing with him to the market in the earthen jar under the clay seal. He talked so much about it that the contents of the earthen jar became the general topic of conversation between the animals, for never had such an article been known at Luri Lura.

When he arrived at the fair the dog walked in with great consequence, and installed himself and his earthen jar in the most central place with much clatter and ostentation. Then he began to shout at the top of his voice, “Come and buy my good food, ”and what with his boastings on the road and the noise he made at the fair, a very large company gathered round him, stretching their necks to have

a glimpse at the strange-looking jar, and burning with curiosity to see the much-advertised contents.

U Ksew, with great importance, proceeded to uncover the jar; but as soon as he broke the clay seal a puff of the most unsavoury and fœtid odour issued forth and drove all the animals scrambling to a safe distance, much to the dog’s discomfiture and the merriment of the crowd. They hooted and jeered, and made all sorts of disparaging remarks till U Ksew felt himself covered with shame.

The stag pushed forward, and to show his disdain he contemptuously kicked the earthen jar till it broke. This increased the laughter and the jeering, and more of the animals came forward, and they began to trample the ktung rymbai in the mud, taking no notice of the protestations of U Ksew, who felt himself very unjustly treated.

He went to U Khla, the governor of the fair, to ask for redress, but here again he was met with ridicule and scorn, and told that he deserved all the treatment he had received for filling the market.

At last U Ksew’s patience wore out, he grew snappish and angry, and with loud barks and snarls he began to curse the animals with many curses, threatening to be avenged upon them all some day. At the time no one heeded his curses and threats, for the dog was but a contemptible animal in their estimation, and it was not thought possible for him to work much harm. Yet even on that day a part of his curse came true, for the animals found to their dismay that the smell of the ktung rymbai clung to their paws and their hoofs, and could not be obliterated; so the laughter was not all on their side.

Humiliated and angry, the dog determined to leave the fair and the forest and his own tribe, and to seek more congenial surroundings; so he went away from Luri Lura, never to return, and came once more to Saddew village, to the house of the family from whom he had bought the offending food. When the master of the house heard the story of the ill-treatment he had suffered from the animals, he pitied U Ksew, and he also considered that the insults touched himself as well as the dog, inasmuch as it was he who had prepared and sold the ktung rymbai. So he spoke consolingly to U Ksew and patted his head and told him to remain in the village with him, and that he would protect him and help him to avenge his wrongs upon the animals.

After the coming of the dog, Man became a very successful hunter, for the dog, who always accompanied him when he went out to hunt, was able to follow the trail of the animals by the smell of the ktung rymbai, which adhered to their feet. Thus the animals lived to rue the day when they played their foolish pranks on U Ksew and his earthen jar at the fair of Luri Lura.

Man, having other occupations, could not always go abroad to the jungle to hunt; so in order to secure a supply of meat for himself during the non-hunting seasons he tamed pigs and kept them at hand in the village. When the dog came he shared the dwelling and the meals of the pig, U Sniang; they spent their days in idleness, living on the bounty of Man.

One evening, as Man was returning from his field, tired with the day’s toil, he noticed the two idle animals and he said to himself—“It is very foolish of me to do all the hard work myself while these two well-fed creatures are lying idle. They ought to take a turn at doing some work for their food.”

The following morning Man commanded the two animals to go to the field to plough in his stead. When they arrived there U Sniang, in obedience to his master’s orders, began to dig with his snout, and by nightfall had managed to furrow quite a large patch of the field; but U Ksew, according to his indolent habits, did no work at all. He lay in the shade all day, or amused himself by snapping at the

flies. In the evening, when it was time to go home, he would start running backwards and forwards over the furrows, much to the annoyance of the pig.

The same thing happened for many days in succession, till the patience of the pig was exhausted, and on their return from the field one evening he went and informed their master of the conduct of the dog, how he was idling the whole day and leaving all the work for him to do.

The master was loth to believe these charges against U Ksew, whom he had found such an active and willing helper in the chase: he therefore determined to go and examine the field. When he came there he found only a few of the footprints of the pig, while those of the dog were all over the furrows. He at once concluded that U Sniang had falsely charged his friend, and he was exceedingly wroth with him.

When he came home, Man called the two animals to him, and he spoke very angrily to U Sniang, and told him that henceforth he would have to live in a little sty by himself, and to eat only the refuse from Man’s table and other common food, as a punishment for making false charges against his friend; but the dog would be privileged to live in the house with his master, and to share the food of his master’s family.

Thus it was that the dog came to live with Man.

Bhogtoram Mawroh is a freelance Cartoonist and Artist. He works as Senior Associate, Research and Knowledge Management at North East Slow Food and Agrobiodiversity Society.

In the early days of the world, when the animals fraternised with mankind, they tried to emulate the manners and customs of men, and they spoke their language.

Mankind held a great festival every thirteen moons, where the strongest men and the handsomest youths danced “sword dances” and contested in archery and other noble games, such as befitted their race and their tribe as men of the Hills and the Forests—the oldest and the noblest of all the tribes.

The animals used to attend these festivals and enjoyed watching the games and the dances. Some of the younger and more enterprising among them even clamoured for a similar carnival for the animals, to which, after a time, the elders agreed; so it was decided that the animals should appoint a day to hold a great feast.

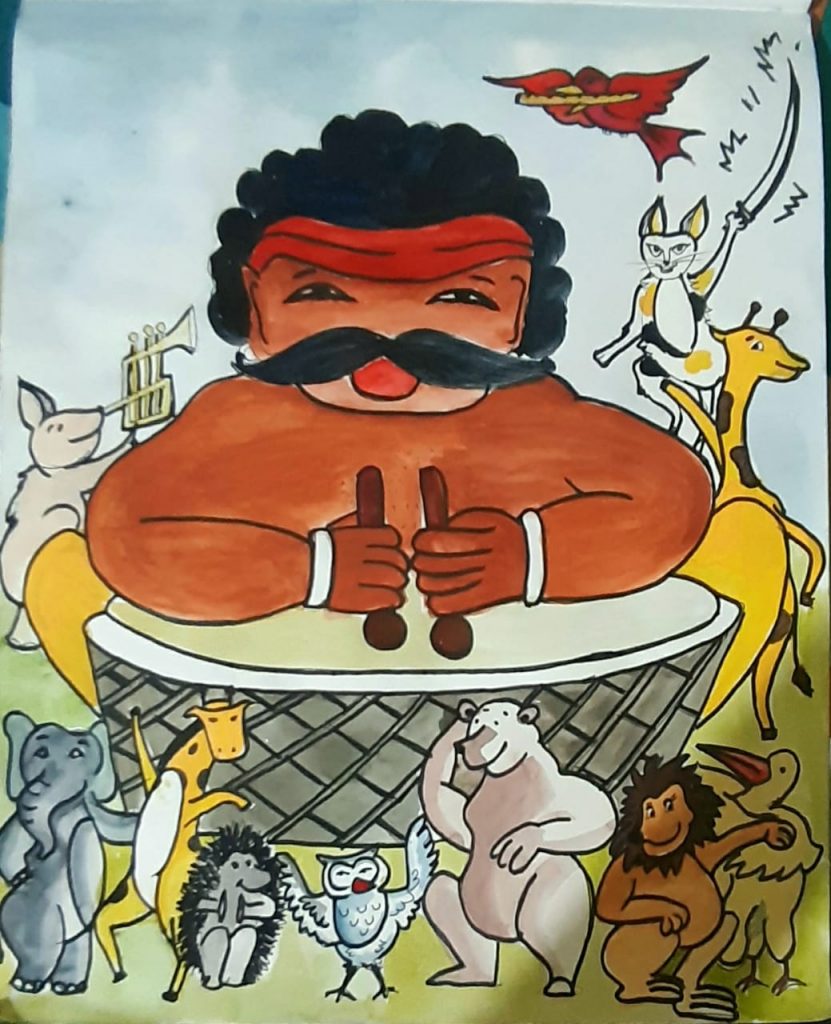

After a period of practising dances and learning games, U Pyrthat, the thunder giant, was sent out with his big drum to summon all the world to the festival. The drum of U Pyrthat was the biggest and the loudest of all drums, and could be heard from the most remote corner of the forest; consequently a very large multitude came together, such as had never before been seen at any festival.

The animals were all very smartly arrayed, each one after his or her own taste and fashion, and each one carrying some weapon of warfare or a musical instrument, according to the part he intended to play in the festival. There was much amusement when the squirrel came up, beating on a little drum as he marched; in his wake came the little bird Shakyllia, playing on a flute, followed by the porcupine marching to the rhythm of a pair of small cymbals.

Every one was exceedingly merry—they joked and poked fun at one another, in great glee: some of the animals laughed so much on that feast day that they have never been able to laugh since. The mole was there, and on looking up he saw the owl trying to dance, swaying as if she were drunk, and tumbling against all sorts of obstacles, as she could not see where she was going, at which he laughed so heartily that his eyes became narrow slits and have remained so to this day.

When the merriment was at its height U Kui, the lynx, arrived on the scene, displaying a very handsome silver sword which he had procured at great expense to make a show at the festival. When he began to dance and to brandish the silver sword, everybody applauded. He really danced very gracefully, but so much approbation turned his head, and he became very uplifted, and began to think himself better than all his neighbours.

Just then U Pyrthat, the thunder giant, happened to look round, and he saw the performance of the lynx and admired the beauty of the silver sword, and he asked to have the handling of it for a short time, as a favour, saying that he would like to dance a little, but had brought no instrument except his big drum.

This was not at all to U Kui’s liking, for he did not want any one but himself to handle his fine weapon; but all the animals began to shout as if with one voice, saying “Shame! ” for showing such discourtesy to a guest, and especially to the guest by whose kindly offices the assembly had been summoned together; so U Kui was driven to yield up his silver sword.

As soon as U Pyrthat got possession of the sword he began to wield it with such rapidity and force that it flashed like leaping flame, till all eyes were dazzled almost to blindness, and at the same time he started to beat on his big drum with such violence that the earth shook and trembled and the animals fled in terror to hide in the jungle.

During the confusion U Pyrthat leaped to the sky, taking the lynx’s silver sword with him, and he is frequently seen brandishing it wildly there and beating loudly on his drum. In many countries people call these manifestations “thunder” and “lightning, ” but the Ancient Khasis who were present at the festival knew them to be the stolen sword of the lynx.

U Kui was very disconsolate, and has never grown reconciled to his loss. It is said of him that he has never wandered far from home since then, in order to live near a mound he is trying to raise, which he hopes will one day reach the sky. He hopes to climb to the top of it, to overtake the giant U Pyrthat, and to seize once more his silver sword.

Agniv Das of Class 7 at Heritage Academy High school at Howrah, West Bengal is a budding artist. He loves to paint, sculpt and is attracted to all forms of visual Art.

He took up online painting classes conducted by Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda Cultural Centre to hone his talent.

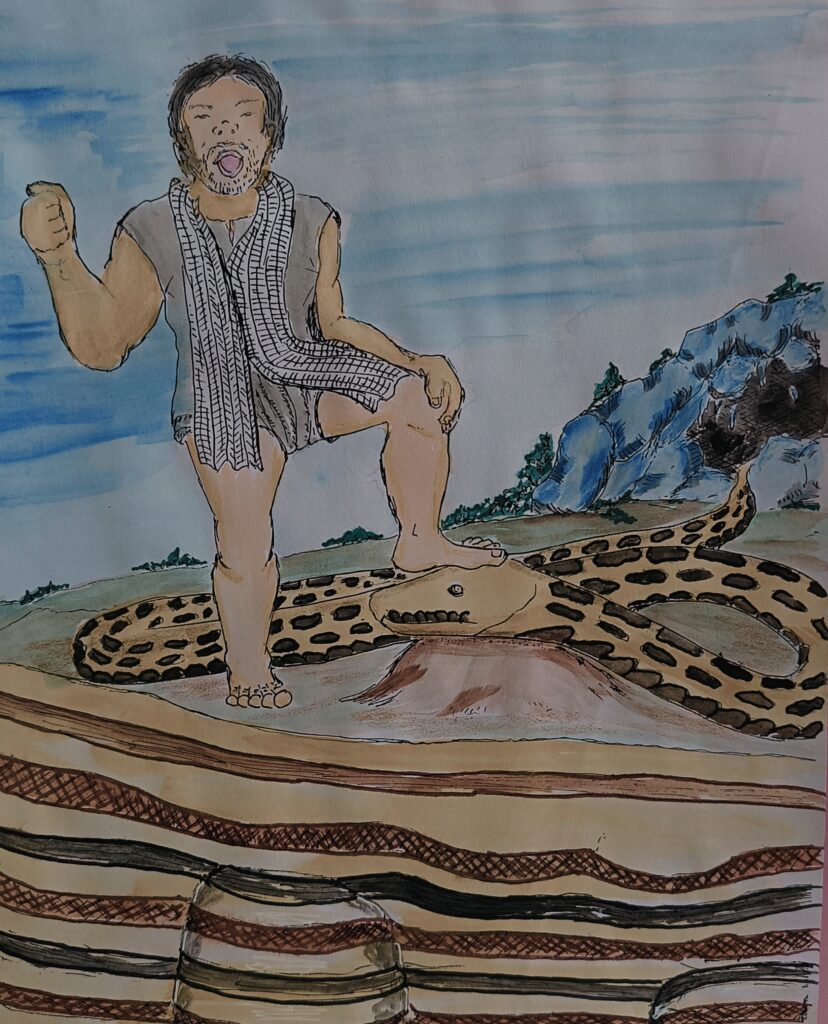

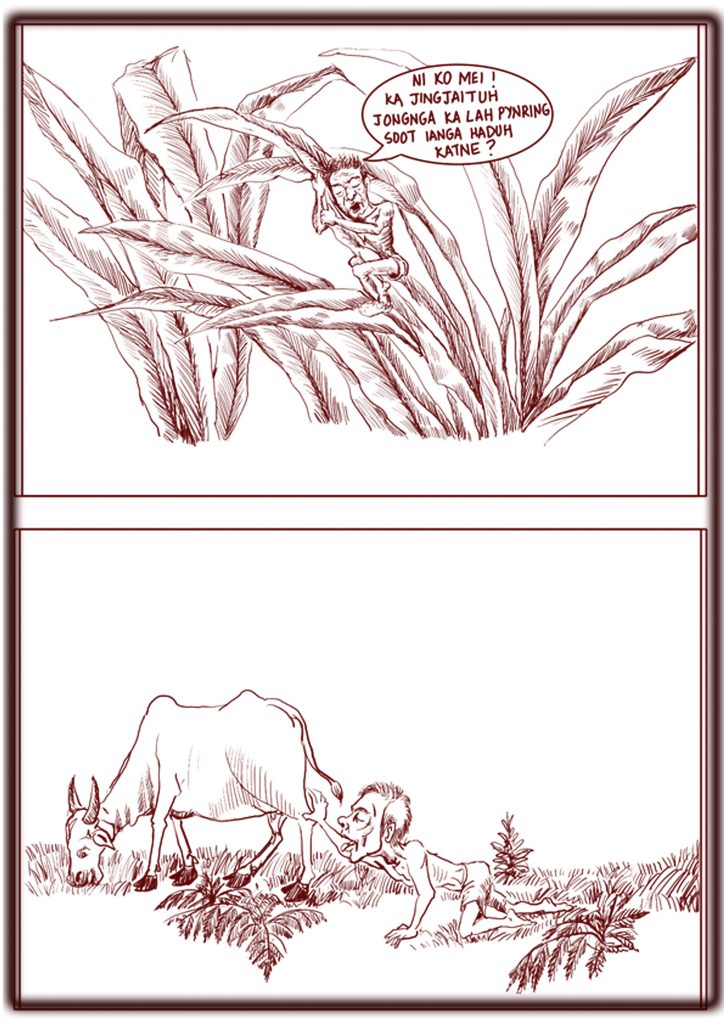

Once there lived a young cowherd, in the rolling lush green hills of the Khasis. As in olden days, and even in today’s village life, every member of a family are allotted certain duties to perform on a daily basis2. U Bahep (a nickname given to the cowherd by his family and known to everyone in the village) was a very lazy young man. Every day by sunrise, there would be hustle and bustle in the village, as most of the people would be up and about doing their daily chores. All, except for Bahep; who even after being roused several times by the shrill voices of his mother and sisters; though awake, would still laze in bed. He was always the last person to get out of bed, and also the last one to start his daily chores and this was known to everyone in the village.

It would almost be noon, by the time he took his cattle out to graze in the open pastures. Upon reaching, he would let his cattle loose and climb onto a nearby tree branch to have a bird’s eye view of his cattle grazing. On more than one occasion, he would have to climb down the tree, to look for a cow that had strayed, and he knew he would be held accountable for any missing cow, which bothered him, as he intended to relax and nap on a tree branch without any disturbance.

He pondered over the same, and came up with a solution that if one did not see a thing happen, then one cannot be held responsible for such incidents. Therefore, to maintain a clear conscience, he devised a way to remove his eyeballs from his eye sockets, which he then wrapped in a leaf, and tied with a length of vine and hung them on a nearby branch. This became a daily habit of his, and at dusk, satisfied with his nap would reach for his eyeballs and put them back in his eye sockets. He would then round up his cattle, and drive them back to their shed. One many occasions, when one or more of the cattle would be missing, and he would be scolded by his father, Bahep would delegate the task of looking for the lost cow(s) to his younger brothers and cousins by bullying and threatening them.

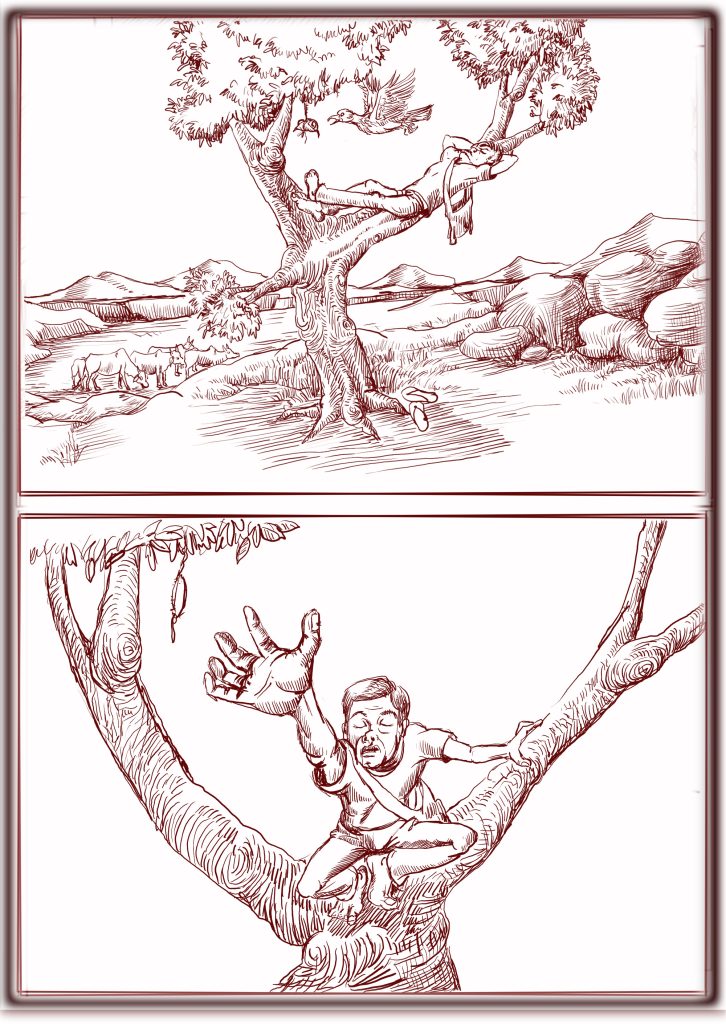

One afternoon, ‘U Khlieng’ a kite, perched upon the tree Bahep was napping on, looking for insects to feed on, and spotted the eyeballs in the leaf hanging by the vines on one of the branches. Thinking it was some sort insect; the kite picked them up and flew away. When the dusk set in, U Bahep started to grope in the dark for the vines in which he had strung his eyeballs in, but alas!! it was all in vain. Bahep, frantic, fell off the tree on the ground below, and desperately kept on groping around in the hope of finding his missing eyeballs. Days, nights, weeks and months passed, and his search continued amongst the pastures and the trees he used to frequent. In this search he strayed and was lost in the middle of nowhere. As time passed, he shrunk in size little by little, as he had little or no food to sustain him, and this took a heavy toll on his entire being, which to adapt, evolved and metamorphosised into a leech without eyes and only a mouth, which he used, to attach himself to the cows to feed on their blood when they grazed in the pastures.

Moral of the story: Don’t be lazy! The cowherd was a strong, healthy and able bodied young man, but due to his laziness he shunned all his responsibilities and was completely careless. His irresponsible and irrational behavior reduced his whole being from a full-fledged human who once herded cows out to graze on the green pastures, to being a leech, which clings to the grasses and latches onto the same cows to feed himself. According to Khasi Folklore this is how a leech, one of Nature’s Creations, came into being.

Swami Vivekananda explained the story of Elephant-God and Mahout-God for seven days.

The question is, why the elephant is God?

There is God inside the elephant so the elephant is God. There is God inside a fish too. Which means there is God inside the good, as well as inside the bad.

In the story, the teacher told the disciple, everything is God. When the mad elephant was advancing, the disciple did not leave as he had strong faith in the words of his teacher, that the elephant is also God. The mahout was shouting, ‘Move away! Move away!’. But the disciple did not move.

The elephant threw him away. But somehow he survived… When he was asked ‘Why didn’t you move?’ he said, ‘Why? The teacher had said that everything is God.’ The teacher said, ‘My child, why didn’t you listen to Mahout-God?’

God resides in everyone as the pure mind. He is inside everyone as the pure intellect. I am an instrument, he is the mechanic. I’m merely a house, He is the homemaker. He is the Mahout-God.

U Swami Vivekananda u la batai shaphang u Blei Hati bad shaphang u Blei Mahut (U Nongñiah Hati) ha ki hynñiew sngi. Ka jingkylli kaba mih ka long, balei la mane Blei ïa u Hati?

Don u Blei hapoh jong u Hati kumta u Hati u dei u Blei bad u Blei u don hapoh jong ka Dohkha ruh kumjuh, kata ka mut ba u Blei u don ha ki ba bha bad kumjuh ha ki ba sniew ruh.

Ha kane ka jingiathuh khana, u Rangbah Niam u la ong ïa la u synran ba kiei-kiei baroh ki dei ki Blei. Ha kawei ka por shikynhun ki Hati lamwir ki la wan, baroh ki synran haba ki la ïohi ïa kane ki la phet hynrei tang uwei napdeng jong ki um shym la khih na ka jaka ba u don namar ba u don ka jingngeit baskhem ïa ki kyntien kiba u Rangbah Niam u kren, ba ngi dei ban pyndem ha u Blei u ba don hapoh jong uno-uno ne kiei-kiei baroh. Wat haba u Mahut u la hylla, “Phet shajngai! Phet shajngai!” hynrei une u synran um shym la patiaw satia.

Kumta, uwei napdeng kita ki Hati u la bret ïa une u synran sharud, hynrei donbok ba um shym la iap. Ki synran ki la wan biang hadien ba u Hati u la phet ki la ïalam ïa u sha u Rangbah Niam, u Rangbah Niam u la kylli ïa u, balei ba um shym la phet na kata ka jaka? U synran u la jubab, “Kynrad, dei maphi hi ba ong ba u Blei u don hapoh jong uno-uno bad kiei-kiei baroh, nga la bud beit ïa ki kyntien jong phi”. U Rangbah Niam u la ong, “Khun jong nga, balei pat phim sngap ïa u Blei Mahut?”.

U Blei u dei trai bad u dei hok ruh ïa uno-uno uba don ka jingmut jingpyrkhat kaba khuid ba suda. U don hapoh jong baroh kiba don ïa ka bor sngewthuh kaba shida. Nga dei tang ka tiar, u dei u Nongshna tiar. Nga dei tang ka ïing, u dei u Nongsumar ïing. Une u dei u Blei Mahut.

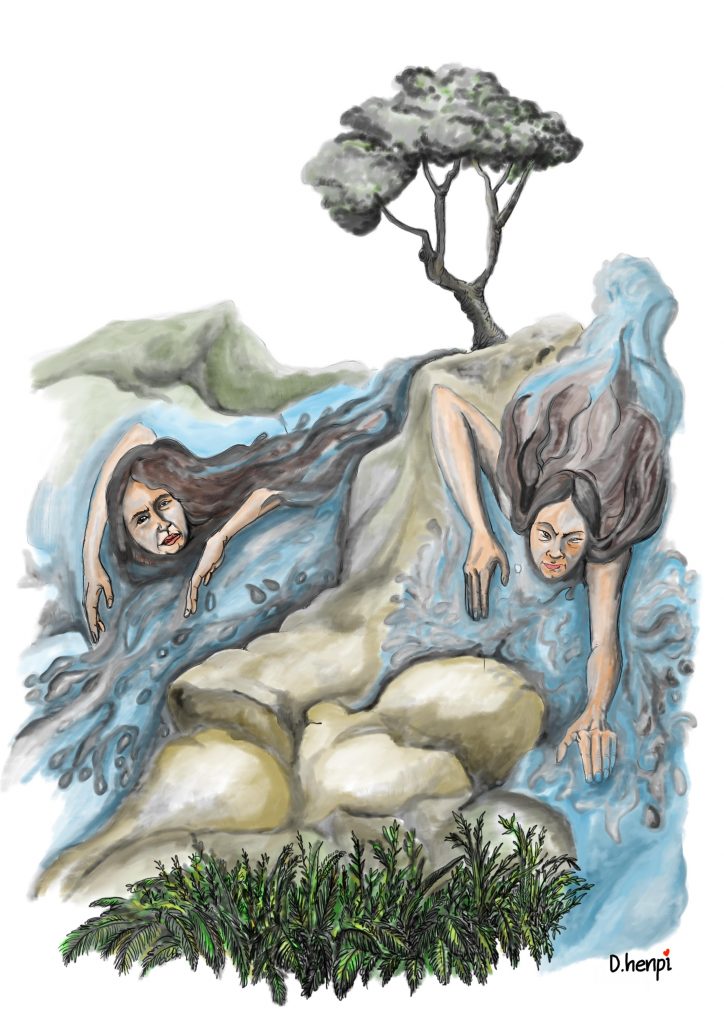

| Ka Iam and Ka Ngot, the twin daughters of the god of Shillong, were two very beautiful beings; they were lively and frolicsome, and were indulged and given much freedom by the family. Like all twins they were never happy if long separated. One day the two climbed to the top of the Shillong mountain to survey the country. In the distance they saw the woody plains of Sylhet, and they playfully challenged one another to run a race to see who would reach the plains first. Ka Ngot was more retiring and timid than her sister, and was half afraid to begin the race; Ka Iam, on the other hand, was venturesome and fearless, and had been called Ka Iam because of her noisy and turbulent disposition. Before the race she spoke very confidently of her own victory, and teased her sister on account of her timidity. |  |

| After a little preparation for the journey the twins transformed themselves into two rivers and started to run their race. Ka Ngot, searching for smooth and easy places, meandered slowly, taking long circuits, and came in time to Sylhet; but not finding her sister there, she [53]went forward to Chhatak, and on slowly towards Dewara. Seeing no sign yet of her sister, she became very anxious and turned back to seek her; and, in turning, she took a long curve which looked in the brilliant sunshine like a curved silver chain, and the Khasis living on the hill-tops, when they saw it, exclaimed with wonder: “Rupatylli, Rupatylli!” (A silver necklace, a silver necklace!) and to this day that part of the river is known as “Rupatylli.” |

Ka Iam, full of vigour and ambition, did not linger to look for easy passages, but with a noisy rush she plunged straight in the direction of Shella, the shortest cut she could find. She soon found, however, that the road she had chosen was far more difficult to travel than she had anticipated. Large rocks impeded her path at many points, and she was obliged to spend much time in boring her way through; but she pitted her young strength against all obstacles, and in time she reached Shella and came in view of the plains, where, to her chagrin, she saw that her sister had reached the goal before her, and was coming back leisurely to meet her. It was a great humiliation, for she had boasted of her victory before the race began, but, hoping to conceal her defeat from the world, she divided herself into five streams, and in that way entered the plains, and joined her sister. The rivers are called after the two goddesses to this day, and are known as “Ka Um Ngot” and “Ka Um Iam” (the river Ngot and the river Iam).

Ever since Ka Ngot won the great race she has been recognised as the greater of the two twins, and more reverence has been paid to her as a goddess. Even in the present day there are many Khasis and Syntengs who will not venture to cross the “Um Ngot” without first sacrificing to the goddess; and when, on their journeys, they happen to catch a glimpse of its waters, they salute and give a greeting of “Khublei” to the goddess Ka Ngot who won the great race.

Dougel Henpilen is an established cartoonist of Shillong who hails from Imphal, Manipur. He dud his schooling from Delhi and later passed from Jamia Milia Islamic university of Lucknow. His cartoons were featured in the very first issue of Kajingshai -the Light—under Larger Than Life Section ![]()