Saturday, March 28, 2020

I can hear the church bells ring for noontime Angelus from our house in Connemara. They are a reminder to repeat a prayer:

The Angel of the Lord declared unto Mary,

And she conceived of the Holy Spirit.

Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee, blessed art Thou . . .

Now and at the hour of our death.

The Divine Mother everywhere is the remover of obstacles and affliction. But in Ireland we pray to Mary in particular to intercede with Jesus her son and with God the Father in times of distress. If there has ever been a time to ask for her help, it is during this Covid-19 pandemic, for those who are sick or facing destitution or otherwise in fear.

The bells of this Catholic church are virtual. Their machine-generated tones, broadcast from loudspeakers, reverberate over the unnaturally still streets of the village.

The following day (Sunday)

Only one or two parishioners are allowed inside the Catholic church to assist the priest for Mass. I am not one of them.

But I can see the priest in my mind’s eye. I can hear him repeat Christ’s words, ‘Do this in memory of me.’ And I ask – is it merely memory? Is not the Last Supper being recreated at this moment? Does not the remembrance by even a single worshipper usher the Lord’s Lila into existence?

Meditating on the Eucharist through the lens of the Gita, we understand the Mass as the eternal sacrifice. The sacramental host, the act of its offering, he who consecrates the host in the inner flame of his being – if you realize the Divine in each of these, you will reach the Divine.

Meanwhile – the little village where I live has eight rumored cases of Covid-19, which, relative to its tiny size, implies an astronomical rate of infection. Naturally people here are fearful. They accept lockdown without reservation. As recent arrivals from abroad, my wife and I are more restricted than the other villagers – we may not enter shops or any public building.

Sunday, April 26, 2020

Now the church is live-streaming Mass with an iPhone for camera. It is reassuring to watch, to picture myself there, though the priest sings off key and his words are difficult to make out as they echo across the near-empty cavern of the church.

A month ago the villagers were just afraid of the virus. Now they are restless to boot. Emotions are raw and ever on the verge of multiplying like uncontrollable audio feedback. Still, these Irish are practical people. In their hearts they are calm, they view the pandemic as one more passing thing. Life will return to the old ways sooner or later. Shops and pubs will reopen, crowds will watch the Galway races elbow-to-elbow, and churches will fill up on the major feast days. This is a conservative place where tradition dies hard, if it ever dies at all. Famines and wars have devastated this part of Ireland, forcing half the population to emigrate and decimating the rest. Those who remained passed down to their descendants a stubborn identity as Catholic Connemara Irish.

For seven centuries, the English colonial rulers suppressed the native Irish and their Catholic religion. They starved the populace, reduced it to serfdom, burned its churches and banished or killed its priests. They cynically offered conversion to Protestantism as a way up and out for those who would repudiate their Catholic faith – but few accepted the offer. Instead, mistreatment by the English bound the Irish forever more tightly to their church.

But he Catholic church in Ireland isn’t what it used to be. I think for Irish society at large that is actually a good thing. Years of unjust persecution conferred immense moral authority on the Irish Catholic church. Subsequent years of arrogance and complacency have effectively squandered that authority. The Church has slid increasingly into irrelevance, causing pews to empty out, vocations to thin, and young people to tell the reporters from Irish Television that the Church means nothing to them.

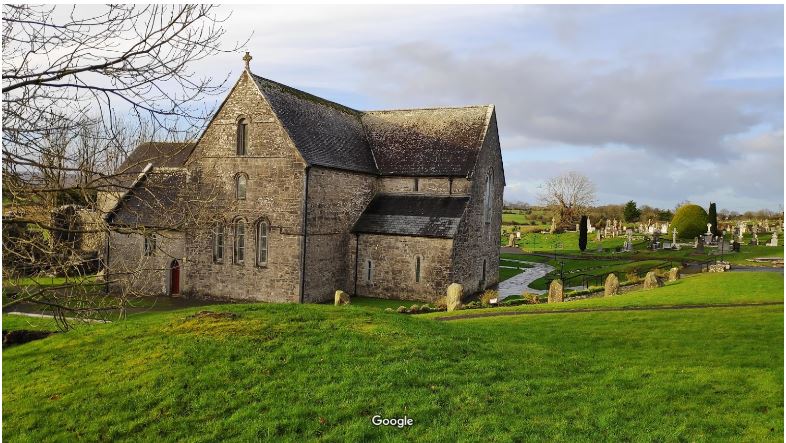

But you wouldn’t know it out here in the country. Most people here identify themselves with a parish – there are several in the area – and go to Mass at least monthly. Though no longer its unrivalled heart, the parish church remans a vital organ of the community.

Catholicism is the de facto religion of the west of Ireland to a degree unimaginable to most twenty-first century Americans. Newspapers and radio stations keep their audiences up to date with local parish services and holy day activities, and host opinion columns by local clergy. In the shops you will find cards for novenas and Holy Communion mixed in with the birthday cards. The ubiquitous Catholic ‘national’ schools are funded by the State.

A half block up the main street is another church in my village – the Church of Ireland, as the Anglican Church in Ireland is called. All over the Republic, the Church of Ireland is struggling, because Protestants are nowadays few, less than one in twenty among the populace. Also, Protestantism is a reminder of the English occupation, though the Irish for the most part no longer bear any ill will toward the English. Once upon a time this was the established church in Ireland, meaning that all Irish, including the Catholic majority, had to tithe in its support. Two hundred years ago on any Sunday morning this little church would be filled with dozens of soldiers from the local British garrison, their bright scarlet uniforms standing out among the plainer clothes of the local landowners and merchants. Now the church is lucky to have a dozen souls in attendance on a given Sunday. But those who attend are committed. The silver lining in the decline of organized religion is that the parishioners who would come to church mainly to be seen have fallen away. Only the dedicated are left in the nearly empty pews.

This is the church I look forward to attending regularly when services are allowed to resume. Its small but ardent numbers call to mind the words of Jesus: ‘For where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.’

. . . . . . . . . .

I was profoundly touched on reading a conversation between Swami Ramakrishnananda and an Irish monk who had converted to Buddhism, disavowing the Catholic faith in which he was raised. To the monk Swami said, ‘God can be attained through all paths. You could have got liberation by following your own religion. You have made a blunder by giving up your own [Catholic] religion and accepting another.’ For the swami, the monk’s blunder lay not in his embracing of Buddhism, but in his rejection of his native religion, where everything he would need to realize God was already at hand.

It would be splendid to see a Vedanta Society grow up in the west of Ireland, bringing to light in this region the teachings of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda, all the while seen as a unity with the traditional Catholic faith. There already are wonderful spiritual riches all about here – people here only need to be awakened to them. If Vedanta can be propagated in such a way as to breathe new life into the ancient Catholic traditions, it will surely catch fire among the latent Irish spiritual seekers now disaffected from their country’s religious past.

Every Indian child growing up is exposed to the stories and myths surrounding such divine figures as Krishna and Rama. The Irish too have access to a vast treasury of spiritual legends, made tangible in the stone crosses, holy wells and monastic ruins from Ireland’s glorious past. I will mention just two places of pilgrimage near where I live that I am fond of visiting: Balintubber and Knock.

Across the lake from my village and some miles to the north is Ballintubber Abbey, where Mass has been said without interruption for eight hundred years. Norman invaders burned the Abbey in the 13th century, English kings further suppressed it, and Cromwell’s soldiers burned down the Abbey roof and surrounding buildings in 1653 – but the Abbey walls remained standing, and Mass continued to be celebrated in the apse of the church. A short walk from the Abbey is St. Patrick’s well, where the legendary fifth-century patron saint of Ireland is said to have baptized his converts (and from which Balintubber, “village of the well”, gets its name). A nearby stone is said to bear the imprint of the saint’s knee.

Several times each year, beginning on Easter Monday, pilgrims assemble here to walk an ancient 22-mile route known as Tóchar Phádraig, or St. Patrick’s Causeway. Their destination is Croagh Patrick, the sacred mountain on whose summit the great founder saint of Ireland fasted for forty days in 441 AD. The priest leading the walk is in high spirits as he points out dozens of spots along the way, each with a story of its own. There is, for example, the ‘Dancora’ (bath of the righteous) where medieval pilgrims, in ritual expression of being cleansed of sin, washed after their pilgrimage to Croagh Patrick before their return home. Hot stones kept the water in the Dancora warm.

It is said that when St. Patrick ended his fast on the mountain summit, he threw a silver bell down the mountain knocking Corra, the mother of all demons, out of the sky and into Lough Nacorra where she drowned. He then banished all the snakes in Ireland into the sea. Some believe that snakes were regarded as symbols of the druids, the high priests of the pre-Christian Celts.

There is no paved path up the steep mountain, only sand, mud, rocks and gravel. In days gone by the especially devout would sometimes climb the mountain on their knees. Halfway up the mountain is a cairn of rocks, atop which you will find a small informal shrine. Coming close you will see it is devoted to the twentieth-century Italian saint Padre Pio, who was known for his extreme piety and service to the sick, and for the stigmata which he tried to conceal but could not, much to the consternation of his superiors in the Church.

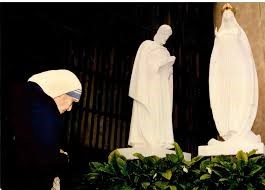

Twenty miles to the northeast of Ballintubber is Knock, where in 1879 fifteen villagers had a vision of Mother Mary on the outer wall of their parish church. Wearing a crown and dressed in white, she was flanked by the Lamb of God, Saint Joseph and St. John the Evangelist. For two hours the villagers were transfixed by the vision as they recited their rosary on bended knee. When Pope John Paul II visited Knock to celebrate Mass one hundred years later, he was greeted by a throng of nearly half a million – about one in ten inhabitants of the country.

Over the years Knock has become a major center of pilgrimage, with a modern basilica that dwarfs the original parish church. It even has its own airport. Nonetheless, in the off-season Knock can be surprisingly quiet and intimate. On one of my visits to the town I was graced with the company of an American sannyasin, who toured the site enthusiastically. Naturally outgoing and spontaneous, he entered into spirited conversation

with one of the many shopkeepers along the main street that sold statues and other memorabilia of the Shrine. I was skeptical that such a shopkeeper would have any interest in a place of pilgrimage beyond the purely mercantile.

But how delighted I was when our swami emerged with several mementoes of Padre Pio presented to him as gifts. The shopkeeper was in fact a sincere devotee of Padre Pio and a devout Christian – as doubtless are countless other merchants and hoteliers at pilgrim centers, grateful for the privilege of dwelling and making their living in a holy place.

Friday, May 29, 2020

Walking home the other day from the village, we noticed the front entrance to the Catholic church was open. Almost on tiptoe we approached and opened the inner door. The apse was empty and still, save for three or four votive candles burning near the main altar. We sat and prayed and meditated awhile. It had been two months since we had last been inside of a place of worship – how cooling was the relief we felt, how soothing the knowledge that we could come back again to sit where the Lord was especially manifest.

Saturday, June 19, 2020

The lockdown continues to lift. We expect services to resume in our Church of Ireland Sunday after next. It will be joyful to see again the little band of parishioners whose acquaintance we had just begun to make earlier this year. The Catholic church in the village has been raising funds for, among other things, repair of the church bells so that we can hear their living musical tones once again. Yet the church will not be able to resume its services for some time in order to respect social distancing. And when it does, how soon will the choir sing together again? When will congregants join together again in the body and blood of Christ?

Nowadays the word ‘together’ evokes hope and fear and anxious caution. The realization is dawning on us all that even after the pandemic has become a distant memory, its impact on our lives will be lasting and disruptive. Things cannot and will not go back to as they were before.

Old forms are dissipating, new forms are in creation, yet the Divine and our relation to Him stay the same, at all times and in every place.