GOING TO HELL?

“And when you die and go to hell, it’s going to be for all eternity. You’ll be tortured there forever. ” To say I was shocked when I heard these words, coming from the mouth of the cousin of a good friend of mine while we were all playing cards together, would be an understatement. I was thirteen years old at the time. My friend’s cousin was an adult, and children of course tend to take what an adult says very seriously. My friend, who was also thirteen, had invited a few of us to join his extended family on a weekend camping trip. We were all having a wonderful time. At one point, a few of us sat down together for a friendly card game. As we played, the conversation had moved to the topic of religion.

All of this occurred in the rural countryside of Missouri, a state in America that has a large population of very conservative Protestant Christians. I was raised Roman Catholic, which made me religiously different from many of my friends and classmates. This difference had never been raised as an issue, until this fateful card game.

A couple of years before the “card game from hell, ” my father had been injured in a truck accident. He was hospitalized for many months, and then he was sent home, where my mother and I cared for him. His injury eventually led to his death, which happened when I was twelve years of age (one year before the camping trip and card game I have just mentioned).

During my father’s ordeal, and following his passing, I had begun to study the religions of the world. While I was still a devout Catholic, I also had an open mind, and wanted to know what many traditions and philosophies had to say about the big questions of life. What happens after we die? Why do we suffer? Does life have a purpose at all?

I was especially focused on the question of the afterlife. I was convinced that my father did not simply cease to exist when his body ceased to function. Indeed, as I saw him suffer through his many profound injuries, I became firmly convinced that we are not this body. If the body can become a prison, as my father’s had, or if it can turn against us, as it does in the case of someone with cancer, then it is something other than us. We are beings of consciousness who experience through the body, but we are not the body. And, not being the body, our existence could well be independent of it.

And indeed, this is what I was taught in the Catholic Church: that the soul and body are distinct, and that the soul continues to another destination after death. Like all Christian traditions, Catholicism teaches that souls in a state of grace reside forever in heaven with God after death, and that souls that are in a state of sin are punished forever in hell. The Catholic Church also has the view that there are souls who enter a third state, called purgatory, which is preparatory to life in heaven, where we are purified of our remaining imperfections.

There were aspects of this view, though, that troubled me. First, I did not feel that I knew of anyone who was so good as to deserve an eternity in heaven, or so evil as to deserve an eternity of punishment in hell. Eternity is a long time: forever. In fact, this was the topic under discussion when my friend’s cousin told me I was going to hell.

Secondly, the concept of hell itself made no sense to me at all. Whenever my parents had to punish me as a child, it was to teach me a lesson, so I would not make the same mistake again, and would do better next time. But an eternal punishment can have no end. It does not improve us. We just suffer forever. What kind of God would inflict an eternal punishment, with no purpose? And if God is all knowing and is our creator, this would mean that God, with full foreknowledge that we would be punished for eternity, went ahead and created us anyway, allowing us to live in a state of sin and then suffering forever. Such a God, in effect, creates beings precisely to punish them for eternity. This is a sadistic, hateful being, and not the God of love taught by Jesus.

The concept of purgatory made a great deal of sense to me, because it acknowledged that most of us are neither wholly good nor wholly evil. Most of the people I have encountered in my life are basically good, but imperfect. They typically do not seek to do harm willfully. I would say this of myself as well.

The problem with purgatory, though, was that it led me to the question, “If we still have imperfections that we need to work out after death, what was the point of this life? What were we doing here, if not working toward greater perfection?” The idea formed in my mind that perhaps we are already in purgatory: that we keep coming back, life after life, and gradually improve until we finally reach perfection and are received into the presence of God.

As I began to learn about the world’s religions, I found this idea echoed in the teachings of traditions like Hinduism and Buddhism: the idea of karma and rebirth, and an ultimate liberation from this process. This rang true to me as being consistent with my experience, with logic, and with the idea of a God who is both loving and just. We need to work out our imperfections. There is no free way out. But we have as many second chances as we need in order to do this.

I was especially drawn to India, and to Hindu traditions in particular, through seeing the movie Gandhi and through listening to the music of the Beatles, especially George Harrison, who was deeply influenced by Hindu traditions and teachings, having been prominently connected to both Transcendental Meditation and ISKCON, as well as the teachings of Paramahansa Yogananda and Swami Vivekananda (whose Raja Yoga he read during a holiday in India in 1966). In both the writings of Gandhi and the music and lyrics of George Harrison, I saw references to the Bhagavad Gita. I thought, “This sounds like a very wise book. I need to find this book! ”

Around this same time, I went with my Grandmother to a local market that was being held in the parking lot of a church (the Methodist Church in our small Missouri town). I accompanied Grandma to many such markets, usually in search of old science fiction novels and comic books. But at this particular market, which I attended around the age of thirteen, I walked to a table with a lot of books and magazines and found, on top of the pile: the Bhagavad Gita! It was a turning point in my life, as I had been thinking of this book but did not know how to go about finding it. I felt almost as if God had left it there for me to find. I picked it up, and the first verses I read were Lord Krishna’s reassurance to Arjuna that when the body dies, the soul continues. Just as a person casts away old and worn-out clothing and puts on a new set of clothing, the soul takes on a new body.

I was astounded to find this ancient book, from another part of the world, which echoed precisely the philosophy to which I was feeling drawn. I have sometimes said that it was like being an extraterrestrial, raised by human beings, who had come across an artifact from his home planet. This book made more sense to me than anything else I had ever read or heard.

So, when I was playing cards on the camping trip and began expressing my views once the topic of religion arose, my friend’s cousin promptly informed me that I was going to hell. I was not only a Catholic. (She believed that all Catholics were going to hell in any case). I was a weird Catholic who believed in rebirth. I was definitely going to hell!

MANY PATHS TO GOD

I had already concluded by that time that the idea of hell did not make any sense. I was also offended by the hypocrisy of someone who claimed to be a follower of Jesus (who said, “Do not judge others”) judging and condemning me to hell. But I was also shaken that an adult would speak in such a way to a child, threatening them with eternal damnation. It felt to me like a form of child abuse.

What made more sense to me, and seemed, again, more consistent with the idea of a just and loving God, was that paths to God must be universally available. It would be up to us, as free beings, to choose whether we took one of these paths. But a loving God would certainly not leave entire civilizations in darkness, as many Christians claimed.

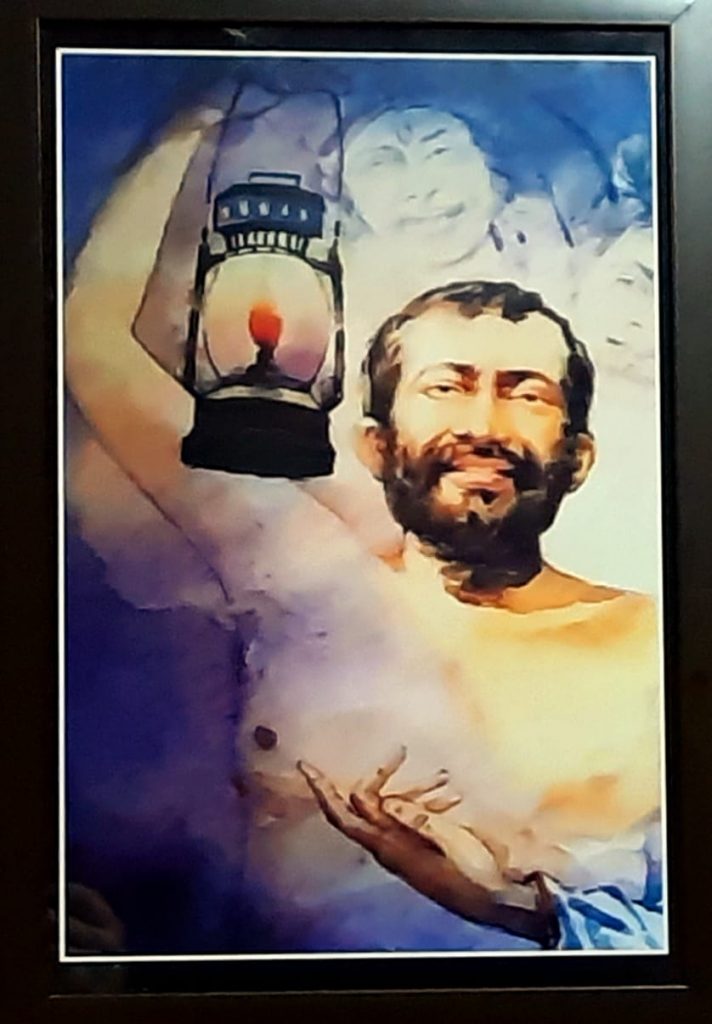

Some time after the card game from hell, as I continued to my exploration of the world’s religions, I was reading Huston Smith’s The Religions of Man and came across the following words of Sri Ramakrishna:

‘I have practiced, ’ said he, ‘all religions–Hinduism, Islām, Christianity–and I have also followed the paths of the different Hindu sects. I have found that it is the same God toward whom all are directing their steps, though along different paths . . . The substance is One under different names, and everyone is seeking the same substance; only climate, temperament, and name create differences. Let each man follow his own path. If he sincerely and ardently wishes to know God, peace be unto him! He will surely realize Him. As with the doctrine of rebirth, and my finding the Bhagavad Gita, reading these words reflecting the Hindu teaching of pluralism–that many paths can and do lead to the ultimate goal–was a transformative experience. This made sense! Much more than the idea of only one true faith, with everyone else in the world going to hell

.

COMING TO SRI RAMAKRISHNA

Early in my spiritual journey, I read the works of many great and wise teachers: not only Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda, but many others as well, like Paramahansa Yogananda, Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts, Swami Muktananda, Swami Rama, and still more, as well as classic texts such as the Upanishads, the Dhammapada, the Daodejing, and so on. I also continued to read and study from within the tradition in which I was born, exploring the works of Thomas Aquinas, Augustine, Anselm, and modern masters like Thomas Merton.

Many years later, after I decided to pursue a career in the study of philosophy and religion and was in the midst of my graduate studies, I met the woman who became my wife, best friend, and fellow traveler on the spiritual path. Mahua, a Bengali Hindu, was born to the tradition of Sri Ramakrishna. Her father was a great devotee of both Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda, while her mother was a similarly great devotee of Anandamayi Ma. It was through this family connection that I came to appreciate the teachings of Sri Ramakrishna at an even deeper level.

Early in my teaching career, after graduate school, the two of us attended a conference, where I presented on Swami Vivekananda’s role in the rediscovery of Buddhism in India. Several swamis and pravrajikas of the Ramakrishna Order also presented at this same conference. I found these presentations to be the best of all, blending both scholarly acumen with a spiritual sensitivity and an appreciation for the depth of Swamiji’s philosophy. My wife and I were both especially drawn to one of these swamis, who eventually consented to become our Guru, giving us diksha, or initiation, into the tradition of Sri Ramakrishna.

I feel that, in this tradition, I have truly come home. I am grateful for my upbringing in the Catholic Church. It gave me a solid foundation in morality and an appreciation for spiritual life. I found, however, the teachings of Christianity too confining, though I nevertheless retain a deep appreciation for it as a valid path to God-realization, as Sri Ramakrishna has taught. When I had ceased to identify with Christianity–ironically, during my time as an undergraduate at a Catholic university, the University of Notre Dame–I felt a sense of freedom, but also a sense of becoming “unplugged” from a source of spiritual energy and inspiration.

Since taking initiation in the tradition of Sri Ramakrishna, I again feel “plugged in. ” I have become convinced that the guru-shishya-parampara, the tradition from teacher to student, tracing back to a great enlightened being, and the guru-shakti, the spiritual energy, that is transmitted via this lineage, are real things. (In the Catholic Church it is called “apostolic succession, ” and is traced back to Jesus. )

As of this writing, it has been twenty years since I met my Guru, and almost twenty years since my initiation. I am grateful every day to God, to my Guru, to my wife, and to the family of all spiritual seekers around the world for the experiences that have led me to this place:

even that miserable card game all those years ago!![]()

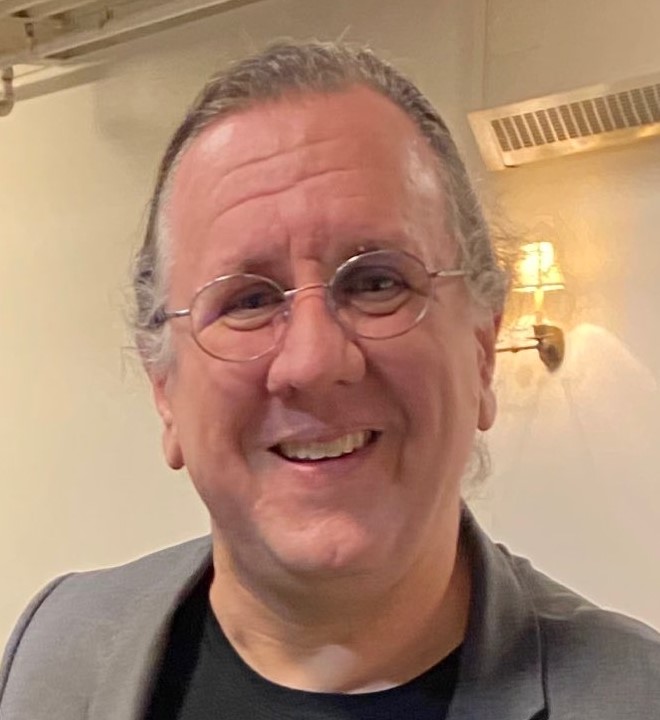

Jeffery D. Long is a religious studies scholar who works on the religions and philosophies of India, particularly Hinduism and Jainism. He is a professor of religion and Asian studies at Elizabethtown College. Dr. Long is associated with the Vedanta Society, New york. A major theme of his work is religious pluralism. Dr. Long has authored several books.

Jeffery D. Long is a religious studies scholar who works on the religions and philosophies of India, particularly Hinduism and Jainism. He is a professor of religion and Asian studies at Elizabethtown College. Dr. Long is associated with the Vedanta Society, D?NAM (the Dharma Academy of North America). A major theme of his work is religious pluralism. Dr. Long has authored several books.